Fecha: julio 2025

Pedro Gete*

Abstract**

This study first documents changes in housing and mortgage markets. Then it analyzes their implications for monetary policy transmission. The main facts are shown for Spain but apply to most OECD economics. Following the financial crisis that began in 2009, there have been a permanent fall in the percentage of individuals owning their own homes, especially for younger groups of the population. The reversal of the drop in homeownership is the rise in the importance of housing investors, both institutional and retail. These investors tend to be rich elder households searching for safety and yield. Moreover, for countries as Spain where variable rate mortgages dominated, there has been a change to fixed-rate mortgages. Using a HANK model of monetary policy that incorporates a rental market and housing investors, we show that these additions have important implications for the transmission channels of monetary policy. Credit and wealth effects are weakened, while those operating through the rental market are strengthened. Two new variables emerge as crucial: the elasticity of substitution between renting and owning, and the spread between safe returns and rental yields. This new channel may help explain recent empirical puzzles, such as restrictive monetary policy being inflationary, or the persistence of «higher for longer» policy rates.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the wake of the pandemic, one word has remained top of mind for most central banks: inflation. To combat it, central banks have worked to slow down economic activity and bring demand more in line with supply. They have raised policy rates and initiated balance sheet reductions. However, in many countries, the economy has not responded as expected—inflation remains high and persistent. Why? This paper documents recent developments in the housing and mortgage markets in Spain, which also have relevance for other countries. It then shows how these developments have altered the transmission channels of monetary policy and may help explain both the persistence of inflation following monetary tightening and the emergence of «higher for longer» policy rates.

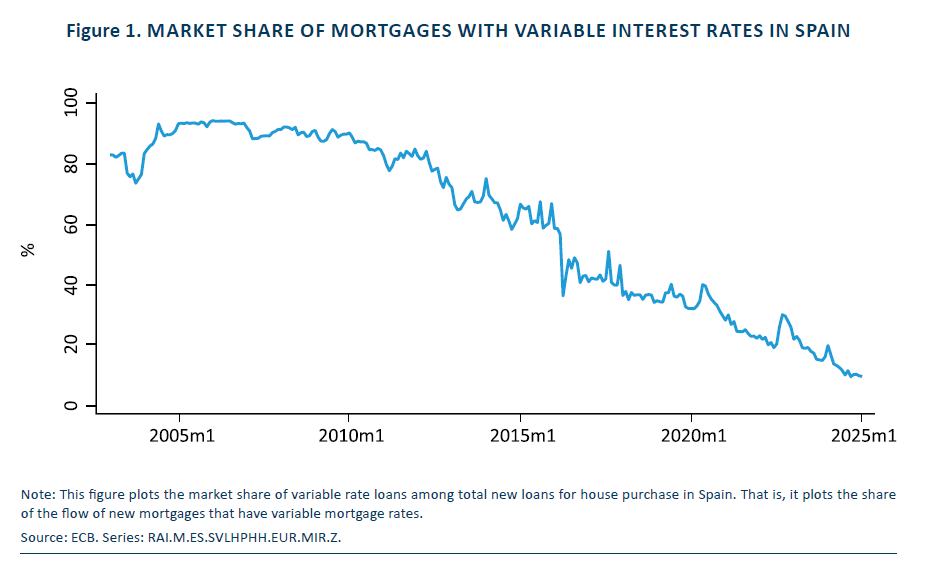

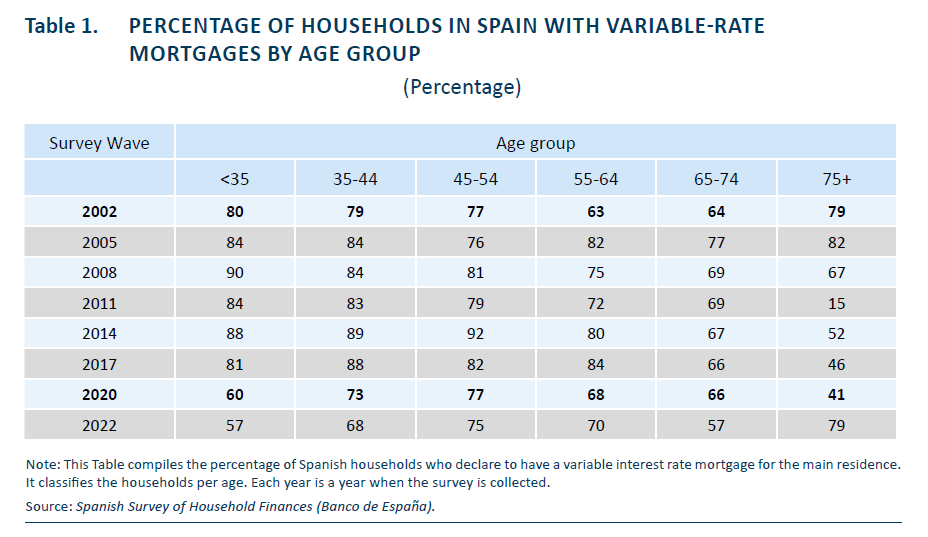

First, we show that in Spain, the share of fixed-rate mortgages has increased dramatically. For example, in 2004, 95% of new mortgages were variable-rate. By June 2022, that share had fallen below 20%. The decline in the use of variable-rate loans is particularly pronounced among both the oldest and youngest age groups. Variable- and fixed-rate mortgages generate different income effects on consumption, both in the aggregate and across types of consumption goods. As a result, the transmission of policy rate changes into the economy depends on the dominant type of mortgage. The literature has proposed models to study the effects of fixed and variable rate mortgages in the economy (Garriga, et al., 2017; Rubio, 2011 or Pica, 2021). Consistent with such models, the increase in variable rate mortgages make the economy less sensitive to monetary policy.

Second, using microdata from the Spanish Household Survey, we document two related developments. First, homeownership declined following the financial crisis, particularly among younger households. By 2021, approximately 76% of the Spanish population were homeowners, representing a decrease of nearly four percentage points since 2014. Second, housing investors have played an increasingly prominent role in the housing market, with most of this growth driven by older, wealthier households seeking yield. These results confirm Carbo-Valverde and Rodriguez-Fernandez (2021) who write this about the Spanish housing market: “a lot of the transactions are not being carried out by households in need of financing but rather investors (including institutional investors) that can afford to pay for their acquisitions without relying on a mortgage”.1 However, nearly all models of monetary policy abstract from rental markets and housing investors. This paper addresses this gap in the literature.

The academic and policy literature typically views the transmission of monetary policy to housing markets as operating through tighter credit conditions (see, for example, Garriga, et al., 2014; Piazzesi and Schneider, 2016). Higher mortgage rates increase the cost of homeownership, making it more expensive for prospective buyers to purchase a home. There is a clear and rapid pass-through from policy rates to mortgage rates. These higher borrowing costs generally dampen demand on both sides of the housing market: potential buyers may delay purchases in anticipation of lower prices or interest rates, while current homeowners may postpone selling to preserve their low locked-in mortgage rates or to wait for a better sale price. As home sales decline, house prices typically fall—but with a lag. However, this classical view of housing in the monetary transmission mechanism weakens when homeownership rates are lower. In such cases, we show that new transmission channels emerge through the rental market.

We analyze an HANK that innovates on two key dimensions.2 The model includes a continuum of households, a representative final-good producer, a continuum of intermediate-good producers, a monetary authority, and a fiscal authority. Households are infinitely lived and subject to uninsurable idiosyncratic labor productivity shocks. Key economic variables—including house prices, rents, the price of non-housing consumption, wages, inflation, and interest rates—are determined endogenously in equilibrium.

The first key innovation of the model is that households can trade housing both as a consumption good (owner-occupied housing) and as an investment asset (rental properties that generate income). Both types of housing are subject to adjustment costs that create illiquidity, and households can borrow against the value of their housing assets. Importantly, the presence of investors in the housing market introduces new economic transmission channels. These individual investors are less sensitive to changes in borrowing costs, but are responsive to shifts in return spreads between real estate and alternative assets such as fixed income securities or bank deposits. This dynamic can lead to counterintuitive outcomes—for example, interest rate hikes generating inflationary pressure through rising rental prices, as increased rental demand meets a contracting supply. We show that the elasticity of housing stock adjustment is a crucial determinant of the economy’s response to monetary policy.

The second key innovation of the model is the explicit inclusion of housing services in the price index—meaning that, as in the data, rent inflation contributes directly to aggregate inflation. This feature has important implications for the persistence and intensity of the central bank’s policy response. We assume the central bank follows a Taylor rule, adjusting the nominal interest rate in response to deviations of inflation from its target. Because the presence of rental market channels and housing investors alters the dynamics of both inflation and output, the central bank’s reaction differs from that in a standard HANK model. In particular, elevated rent inflation compels the central bank to keep interest rates higher for longer.

Thus, to recap, this paper shows that a model incorporating both a rental market and housing investors can produce inflation dynamics that are notably resistant to conventional monetary tightening. In particular, the presence of housing investors—who respond more to return spreads than to borrowing costs—and the role of rents in the overall inflation index create a situation where interest rate hikes may not produce the expected disinflationary effects. Instead, higher rates can constrain housing supply by discouraging new construction or sales, while also increasing demand for rental housing as homeownership becomes less affordable. This combination puts upward pressure on rents, which feeds directly into measured inflation. As a result, inflation remains elevated despite tighter policy, forcing the central bank to sustain higher interest rates for longer than it would under standard assumptions. These findings suggest that structural features of the housing market, particularly the rise in rental demand and investor activity, can fundamentally alter the transmission of monetary policy. Recognizing and accounting for these channels is therefore essential for designing effective policy in modern economies.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the Encuesta Financiera de las Familias (EFF), the main household-level dataset used in the analysis, and documents the evolution in the use of fixed- and variable-rate mortgages in Spain. Section 3 examines trends in homeownership, compares Spain to similar countries, and places particular emphasis on the growing role of housing investors. It presents both descriptive evidence and regression analysis to identify the key drivers behind these developments. Section 4 develops a Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian (HANK) model that incorporates critical features of the housing market, including rental dynamics and investor behavior. It begins by comparing the classical role of housing in the monetary policy transmission mechanism with the new channels that emerge in the presence of a rental sector and housing investors, using demand and supply diagrams to build intuition. The section then employs the full model to analyze the implications of the empirical findings for monetary policy. It shows how rent inflation, driven by structural changes in the housing market, can contribute to aggregate inflation and lead the central bank to maintain elevated interest rates for a prolonged period. Finally, Section 5 concludes.

2. DATAbase

The Encuesta Financiera de las Familias (EFF) is a financial survey conducted by the Banco de España to analyze the economic and financial situation of Spanish households. Initiated in 2002 and repeated periodically since then, the EFF has become a key instrument for understanding the structure and dynamics of household finances in Spain. It gathers extensive micro-level data on income, consumption, savings, real and financial assets, as well as liabilities such as mortgages, consumer loans, and other forms of debt. This rich dataset provides a comprehensive snapshot of how Spanish households accumulate and manage wealth over time.

One of the distinctive features of the EFF is its deliberate oversampling of high-wealth households. This methodological choice allows the survey to capture the upper tail of the wealth distribution more accurately, which is often underrepresented in standard surveys. In the context of broader European efforts, the EFF is Spain’s contribution to the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS), coordinated by the European Central Bank, facilitating international comparisons and cross-country analysis of household finance. We conduct such comparisons with a few European countries.

3. Variable- vs. Fixed-Rate Mortgages in Spain

This section documents that in recent years, Spain has been undergoing a significant shift in its mortgage market, transitioning from a predominance of variable-rate mortgages to a growing preference for fixed-rate loans.3

Figure 1 plots the market share of variable rate loans among total new loans for house purchase in Spain. That is, it plots the share of the flow of new mortgages that have variable mortgage rates. The data are astonishing. Spain has transitioned from 90% of the new mortgages being issued at variable rates in 2005 to less than 20% share in 2025.

Table 1 presents the percentage of Spanish households with variable-rate mortgages for their primary residence, disaggregated by age group across survey waves from 2002 to 2022. The data reveal significant temporal and generational dynamics in mortgage structure, shaped by changing financial conditions and demographic factors. Across nearly all survey years, younger age groups—particularly those under 35—consistently report the highest incidence of variable-rate mortgages. This likely reflects both greater risk tolerance among younger borrowers and more limited access to fixed-rate products at the point of entry into the housing market. The mid-2000s mark a period of widespread use of variable-rate mortgages across all age groups, peaking in 2008 when the under-35 group reached 90%. Following the global financial crisis, however, there is a visible decline in the use of variable-rate loans, especially among the oldest and youngest age groups. For example, in 2011, only 15% of households aged 75 and over held variable-rate mortgages—a stark drop from previous years. This decline continues for most cohorts through 2020. By 2022, there is a notable divergence: younger households (under 35) show a substantial drop to 57%, whereas the 75+ cohort spikes back up to 79%. Meanwhile, middle-aged groups (35–64) maintain relatively high and stable levels of variable-rate mortgage use, hovering between 68% and 75%, suggesting that these cohorts remain more exposed to interest rate fluctuations over time.

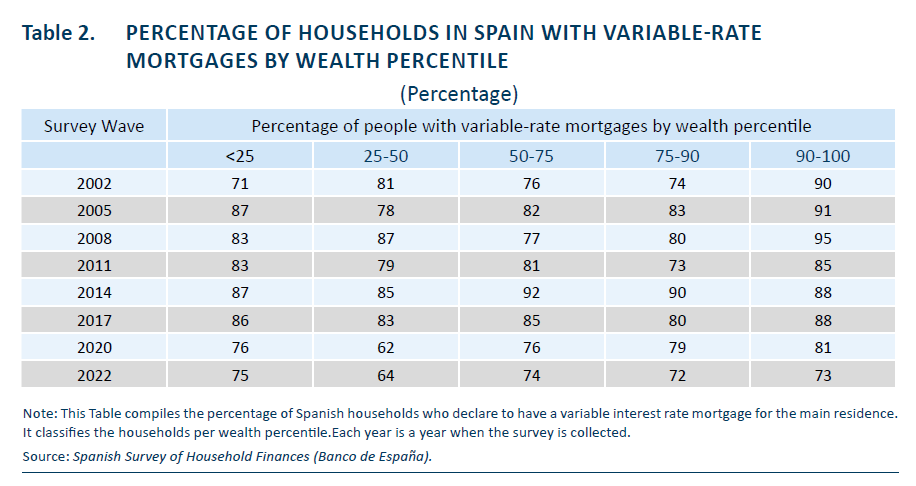

Table 2 shows the percentage of Spanish households with variable-rate mortgages for their main residence, categorized by wealth percentiles across survey waves from 2002 to 2022. The data reveal a generally high incidence of variable-rate mortgages across all wealth brackets, with notable variations over time and across wealth levels. In the early 2000s, households in the top wealth decile (90–100 percentile) consistently exhibited the highest share of variable-rate mortgages, reaching 95% in 2008. This suggests that wealthier households were more likely to take on interest rate risk, potentially due to better financial buffers or access to more favorable credit terms. Over time, the data indicate a gradual decline in the prevalence of variable-rate mortgages across all wealth groups, especially after the 2008 financial crisis. By 2022, the percentages dropped notably for all percentiles, particularly in the 25–50 and 50–75 ranges, which fell to 64% and 74%, respectively. The wealthiest households also reduced their exposure to variable-rate mortgages, though they still maintained relatively high levels (73% in 2022), perhaps reflecting continued access to flexible financial products or strategic borrowing choices amid fluctuating interest rate environments.

Interestingly, Table 2 shows that lower-wealth households (below the 25th percentile) maintained a relatively high reliance on variable-rate mortgages throughout the period, with only a modest decline from 87% in 2014 to 75% in 2022. This persistent dependence may reflect limited bargaining power or restricted access to fixed-rate alternatives. In contrast, middle-wealth households (50–75 percentile) showed sharper variability over the years, peaking at 92% in 2014 and decreasing to 74% by 2022. These fluctuations may indicate greater sensitivity to market conditions or policy interventions influencing mortgage structure choices. Overall, the data indicate a historically widespread reliance on variable-rate mortgages in Spain, which has shifted over time—though with differing dynamics across wealth groups.

Traditionally, Spanish borrowers favored variable-rate mortgages due to their initially lower interest rates and the ability to benefit from falling benchmark rates, such as the Euribor. However, as ECB and its Quantitative Easing programs kept rates low, many Spaniards moved into fixed-rate mortgages to lock-in the low rates. Moreover, in the wake of economic uncertainties and increasing interest rate volatility, consumers have become more cautious. The appeal of long-term financial stability and predictable monthly payments has driven a surge in fixed-rate mortgage adoption. This transformation is also supported by structural changes within the banking sector and regulatory adjustments. Financial institutions have started to actively promote fixed-rate products, aligning with European trends and responding to evolving risk management strategies. The European Central Bank’s monetary policies and forecasts of rising interest rates have further reinforced the attractiveness of fixed-rate options. As a result, a substantial portion of new mortgages in Spain today are issued at fixed rates—a stark contrast to two decades ago. This marks a fundamental evolution in the Spanish housing finance market.

As Subsection 5.1 will discuss, classical models of monetary policy show that this transition into fixed-rate mortgages alters the effects of monetary policy on consumption, a topic of great importance for the Spanish economy (see for example, Torres 2023). Households with fixed-rate mortgages react less to monetary policy because their mortgage payments remain constant over time, regardless of fluctuations in the central bank’s policy rates. When a central bank, like the European Central Bank (ECB), raises or lowers interest rates, fixed-rate borrowers are insulated from these changes: their loan agreements lock in the interest rate for the entire term of the mortgage.

4. Homeownership Dynamics and Housing Investors

4.1. Spain

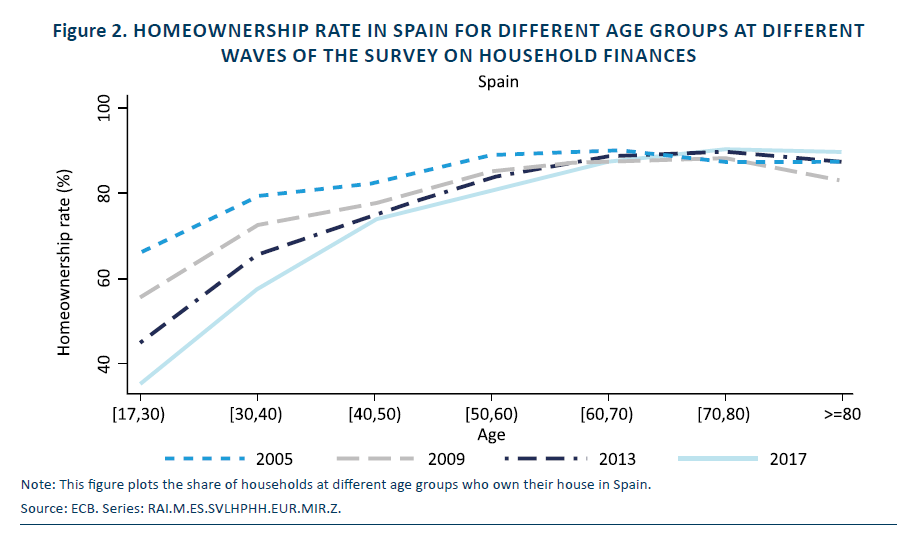

Figure 2 examines the evolution of homeownership rates in Spain using data disaggregated by age group from 2005 to 2017. The analysis reveals a clear downward trend in homeownership among younger cohorts, alongside relative stability among older households. These shifts suggest structural changes in the Spanish housing market, with important implications for the transmission of monetary policy, as discussed in later sections.

Homeownership among individuals aged 17 to 30 declined markedly over the observed period, falling from over 60% in 2005 to approximately 35% by 2017. This sharp contraction reflects worsening housing affordability, stricter credit conditions, and elevated youth unemployment in the years following the global financial crisis. Economic precarity and tightened lending standards appear to have delayed or prevented market entry for younger households, resulting in an increased reliance on rental housing.

Among individuals aged 30 to 50, the data show a flattening of the age-homeownership curve, especially after 2009. While older cohorts within this group historically experienced a steady progression into homeownership, more recent patterns suggest stagnation. This may reflect a combination of delayed household formation, income constraints, and limited access to mortgage financing, which have reduced upward mobility in the housing market. In contrast, homeownership remains persistently high among those aged 60 and above, with rates exceeding 85% across all survey years. This cohort benefited from more favorable macroeconomic conditions and policy environments during their peak earning years.

The most significant inflection point in the time series occurs between 2009 and 2013, coinciding with the aftermath of the financial crisis. This period was marked by a sharp contraction in credit availability and a collapse in the real estate market, which disproportionately affected younger and middle-aged households. These developments led to a decline in new mortgage originations and a persistent drop in homeownership rates. These findings suggest a structural transformation in Spain’s housing system. The declining incidence of homeownership among younger cohorts points to a shift not only in economic circumstances but also in tenure preferences. As Spain continues to transition from a variable-rate to a fixed-rate mortgage market, the implications of changing borrower profiles will be increasingly relevant for the effectiveness of monetary policy.

4.2. Other Countries

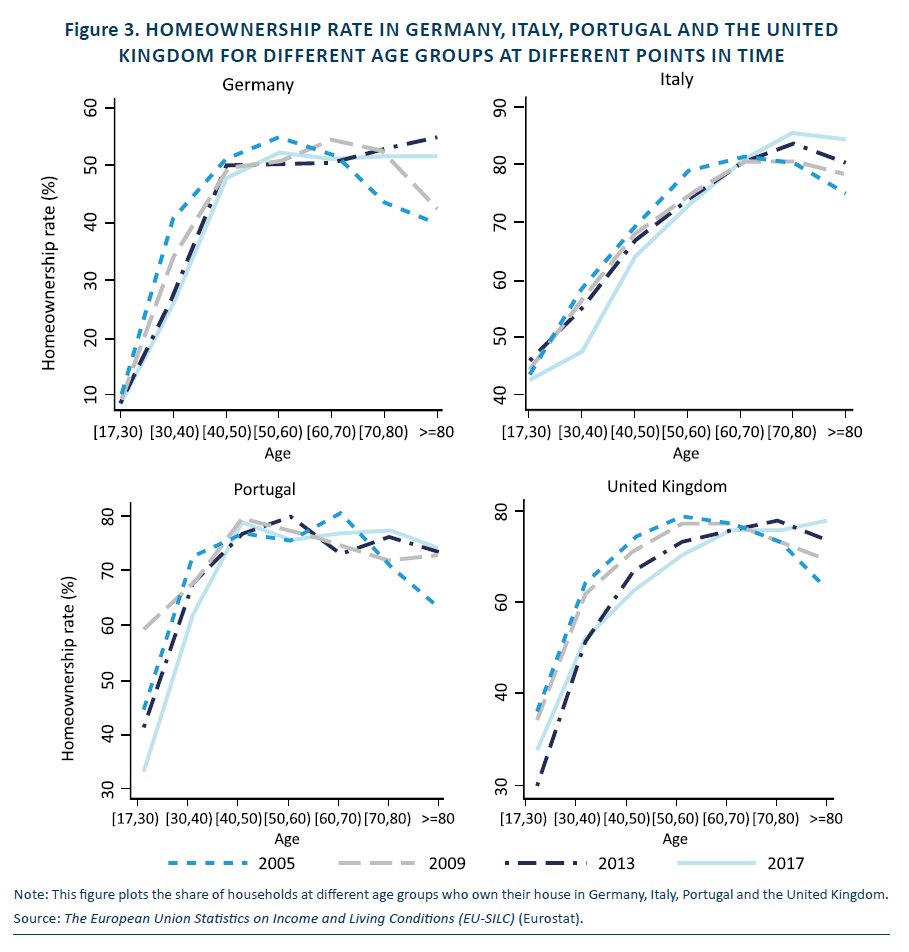

Figure 3 plots the time series of homeownership for Germany, Italy, Portugal and United Kingdom. Like Figure 2, it looks for multiple age groups. Figure 3 reveals marked differences in homeownership patterns both across countries and generations, with significant implications for housing policy and intergenerational equity.

In Germany, homeownership rates remain comparatively low across all age groups, particularly among the younger cohorts. While ownership increases steadily with age, peaking around retirement, the 2017 data show a noticeable decline in ownership for individuals under 60 compared to previous years. This trend suggests growing barriers to entry into homeownership for younger Germans, potentially due to rising housing costs, stricter credit conditions, or a persistent preference for long-term renting, which is culturally and institutionally supported in Germany.

Italy, by contrast, exhibits high and relatively stable homeownership rates across all age groups over time. The ownership rate climbs gradually with age and remains elevated even in the older cohorts, peaking in the 70–80 age range. There is little evidence of significant temporal change between 2005 and 2017, indicating a resilient structure of homeownership, likely supported by strong family networks and a tradition of property inheritance. The stability may also reflect a more consistent housing market and policies that support home retention across generations.

Portugal also demonstrates high levels of homeownership, though with slightly more fluctuation across time and age groups than Italy. Young Portuguese adults saw moderate improvements in ownership up to 2009, but a decline appears in the 2017 data, especially among those under 40. Ownership among older age groups remains robust. This may indicate the lingering impact of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent austerity on younger households’ ability to access the housing market, even as older cohorts retained their homes.

The United Kingdom shows that while overall homeownership rates increase with age, post-Financial crisis there is a sharp decline in ownership among younger and middle-aged adults compared to earlier years. This suggests that structural challenges—such as housing affordability, supply shortages, and stricter mortgage lending standards—have disproportionately affected younger generations. The UK appears to be undergoing a generational shift away from the historically embedded ideal of owner-occupation.

Taken together, the data underscore a broader trend of declining homeownership among younger age groups across several countries, albeit to varying degrees. These patterns reflect a complex interplay of economic pressures, housing market dynamics, and institutional frameworks.

4.3. Housing Investors in Spain

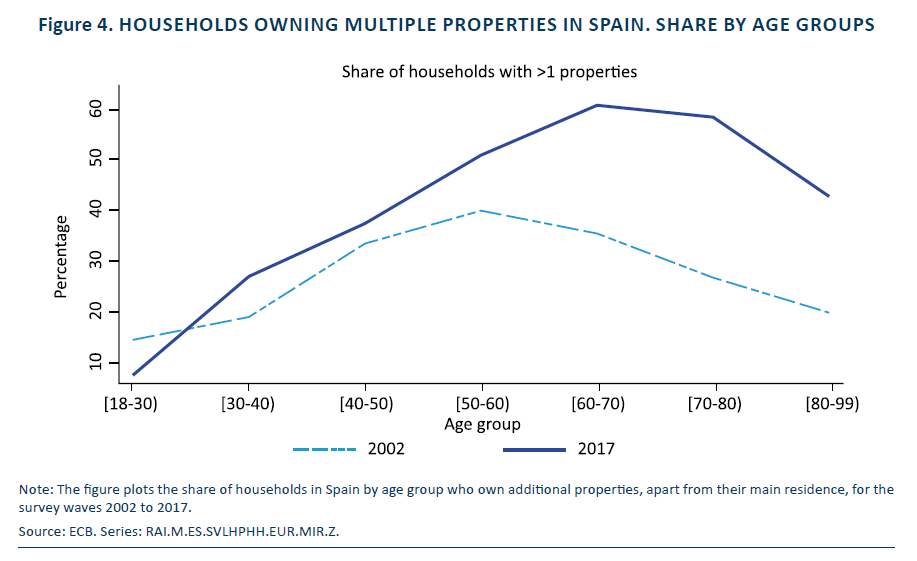

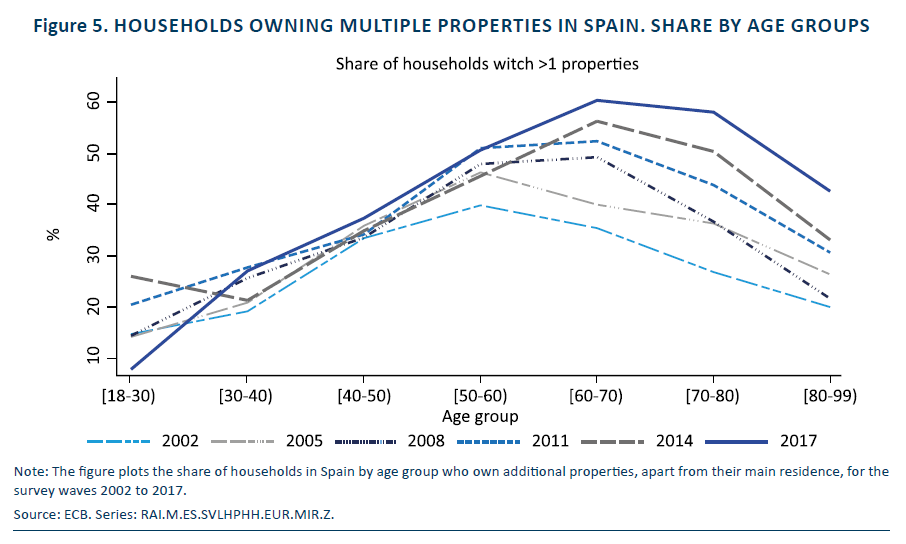

As homeownership rates decline among young households in Spain, a key question arises: who is purchasing the housing stock? Figure 4 presents the share of Spanish households owning more than one property in 2002 and 2017, disaggregated by age group. The data confirm a strong positive correlation between age and the likelihood of owning multiple properties in both years. In 2002, the proportion of households with more than one property increases steadily from the youngest age group (18–30) to those aged 60–70, after which it slightly stabilizes. This pattern suggests that property accumulation is closely tied to life-cycle factors such as income growth, financial stability, and inheritance. By 2017, the overall shape of the distribution remains similar, but several shifts are apparent. Most notably, the share of households with multiple properties increased among the middle-aged groups—particularly those aged 40–60—suggesting greater engagement with property investment in these cohorts.

Figure 5 confirms the general pattern post-financial crisis. The elder households not only own their main residence, but the recently have substantially increased their holdings of real estate. For example, 50% of households between 60 and 70 years old owned more than one properties in 2000, whereas this percentage exploded to 70% in 2014.

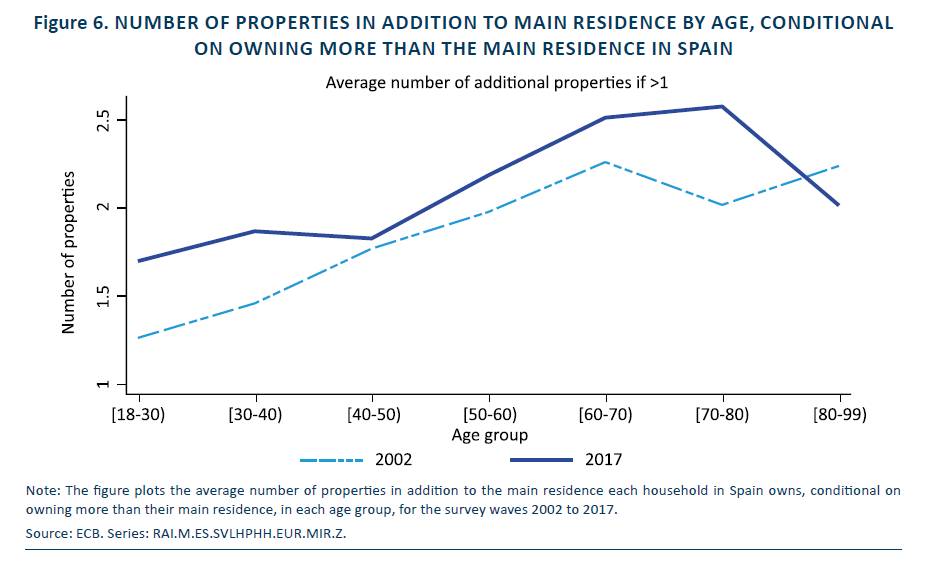

Figure 6 illustrates the average number of additional properties held by Spanish households—conditional on owning more than one property—across age groups in 2002 and 2017. A clear age gradient is evident in both years, with older cohorts tending to own a higher number of additional properties compared to younger ones. In 2002, property accumulation beyond the primary residence was most pronounced among households aged 70–80 and 80–99, with averages exceeding two properties, while younger age groups held closer to 1.5 on average. This reflects a life-cycle accumulation effect, where property ownership builds up over time due to investment motives. By 2017, although the overall pattern remains, some notable shifts occur. The average number of properties each household owns increased over time for the elder households, and that it remained unchanged or even decreased for the younger households.

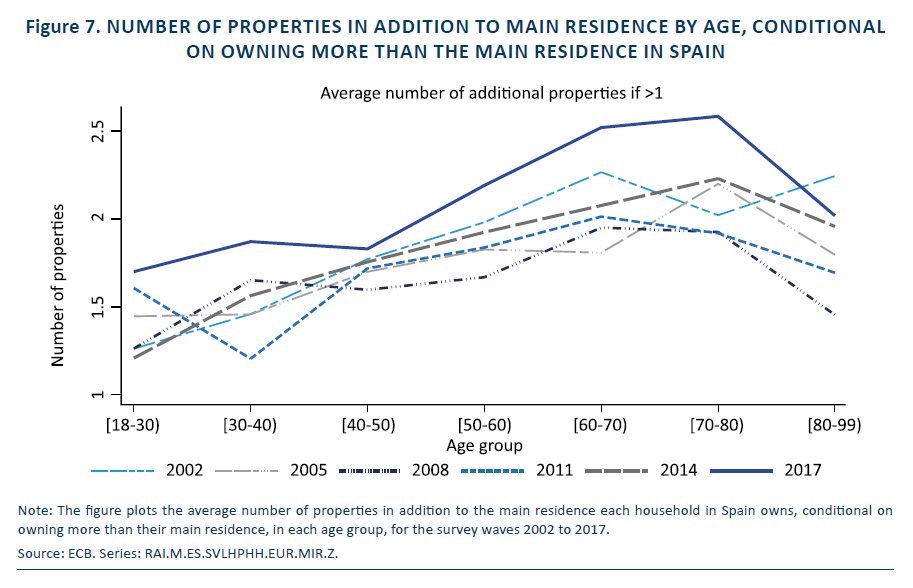

Figure 7 corroborates that older—and typically wealthier—households are the ones purchasing the housing stock that younger households are no longer acquiring. These additional properties are likely being used as investment assets. In effect, older households increasingly act as landlords, renting homes to younger households who are unable to access homeownership.

4.4. Drivers of Housing Investments

The previous figures reveal striking shifts in patterns of property ownership among households. To rigorously assess the factors driving households to own multiple properties, we estimate a series of regressions using data from the Encuesta Financiera de las Familias (EFF). The EFF provides repeated cross-sectional survey data, where a different sample of households is surveyed in each wave using a consistent set of questions, allowing for comparability over time. Each wave is representative of the national household population, enabling robust analysis across survey years.4 Our main empirical strategy employs the full pooled sample and treats the data as repeated cross-sections.

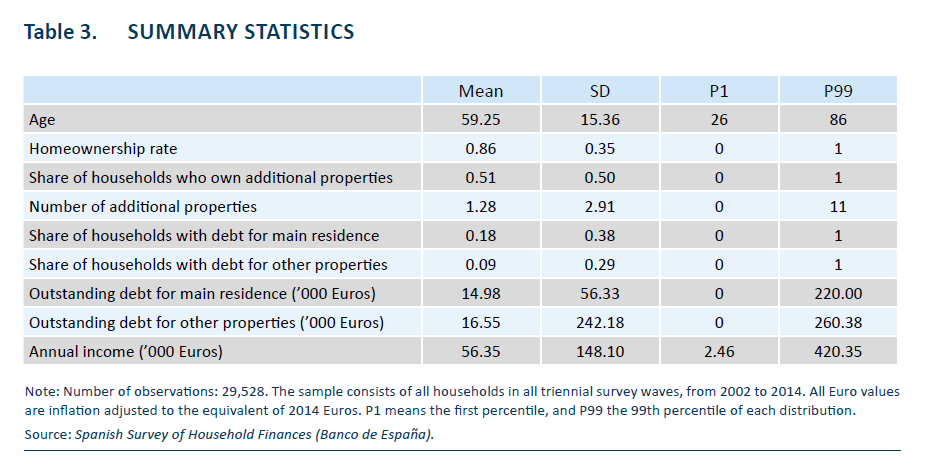

Table 3 describes the sample. It provides summary statistics for the full sample of Spanish households surveyed between 2002 and 2014, capturing the key phases of the economic boom and subsequent bust. The data offer a broad view of housing-related characteristics, debt, and income. The average age of household respondents is 59.25 years, suggesting that the sample includes a substantial proportion of late-career or retired individuals. Homeownership is widespread, with an average rate of 86%, reflecting Spain’s historically high levels of owner-occupation. Additionally, more than half of households (51%) own at least one additional property, pointing to the prevalence of real estate as an investment vehicle. Among those with additional properties, the average number is 1.28, but the standard deviation of 2.91 and a 99th percentile value of 11 highlight considerable skewness and concentration at the top end of the distribution. This suggests that while many households may own a second home or inherited property, a smaller subset holds significantly larger property portfolios.

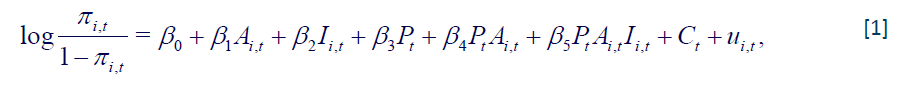

Specifically, we estimate the following logistic regression:

where i indexes the household and t

indexes the household and t the year of the survey wave.

the year of the survey wave.

![]() denotes the probability of household

denotes the probability of household  i owning multiple properties at time t

i owning multiple properties at time t

.

.  Pt is a binary variable that takes the value of one post-crisis, that is, for the survey waves 2011 and 2014, and the value of zero pre-crisis, that is, for the waves 2002, 2005 and 2008. Ai,t

Pt is a binary variable that takes the value of one post-crisis, that is, for the survey waves 2011 and 2014, and the value of zero pre-crisis, that is, for the waves 2002, 2005 and 2008. Ai,t is the age of the reference person of the household. The reference person is the one who chiefly deals with the household’s finances. Ii,t

is the age of the reference person of the household. The reference person is the one who chiefly deals with the household’s finances. Ii,t

is the household’s annual income. This is calculated as the sum of labor and non-labor income for all household members. We adjust the total income for inflation, so all values are in 2014 Euros. The final values of income are in thousand of Euros.

is the household’s annual income. This is calculated as the sum of labor and non-labor income for all household members. We adjust the total income for inflation, so all values are in 2014 Euros. The final values of income are in thousand of Euros.  Ct denotes the controls, which are dummies for each survey wave.

Ct denotes the controls, which are dummies for each survey wave.

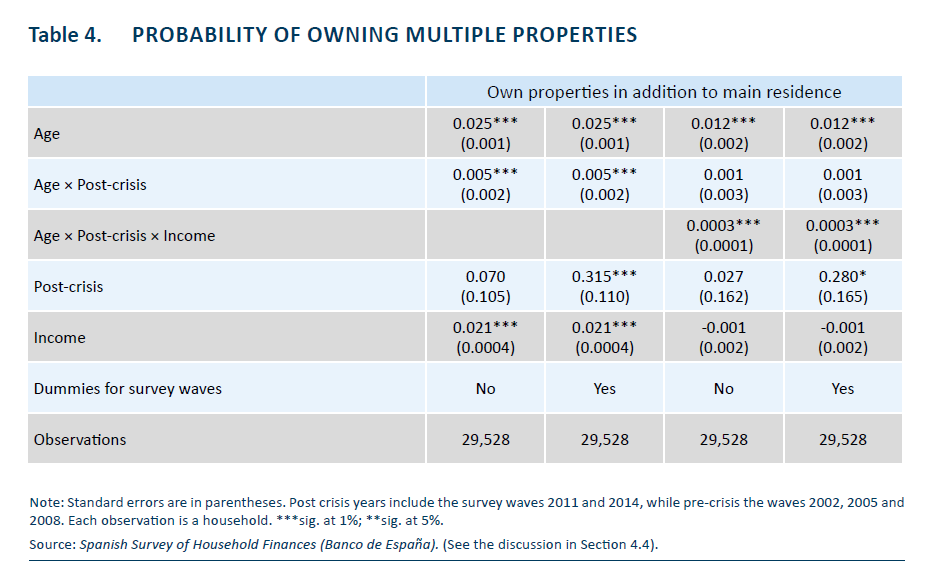

Table 4 shows the results of the estimation of the logit model (1). Across all specifications, age shows a consistently positive and statistically significant association with the probability of owning additional properties. In columns (1) and (2), the coefficient on age is 0.025, indicating that each additional year of age increases the likelihood of multi-property ownership by 2.5 percentage points, holding other factors constant. This suggests that property accumulation is closely tied to life-cycle dynamics, such as income growth, asset accumulation, or inheritance over time.

The interaction between age and the post-crisis period is also positive and statistically significant in columns (1) and (2), with a coefficient of 0.005. This implies that the positive age effect was even stronger after the crisis, potentially reflecting a concentration of property wealth among older cohorts who were less affected by financial constraints or who capitalized on post-crisis housing market conditions. However, once income interactions are introduced in columns (3) and (4), the significance of this age × post-crisis interaction disappears, suggesting that income plays a mediating role.

Indeed, the key coefficient of interest, the triple interaction term—age × post-crisis × income—is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level in both column (3) and (4). This implies that higher-income households benefited more strongly from age-related increases in property accumulation during the post-crisis period. In contrast, income alone is only significant in the first two specifications and becomes insignificant once interactions are introduced, indicating that income effects are largely conditional on timing and age.

The coefficient on the post-crisis dummy itself varies: it is not significant in column (1) but becomes large and statistically significant (0.315) in column (2) when survey wave dummies are included. This finding points to heterogeneity in the crisis effect across different periods, possibly reflecting shifts in credit availability, tax treatment, or property values over time.

Overall, Table 4 reveals that the likelihood of owning multiple properties increases with age, and that this effect is magnified in the post-crisis period—especially among higher-income households. That is, those more willing to invest in housing in search for yield. Next, we study the implications of these facts for monetary policy.

5. Housing and Monetary Policy: the Classic Channel and the New Rental Channel

The preceding evidence clearly shows that Spain—along with many other economies—has experienced a growing importance of the rental market, driven by declining homeownership rates and a rise in housing investment activity. This section examines the implications of these structural shifts for the transmission of monetary policy. We begin by reviewing the classical transmission channel through housing, highlighting how monetary policy typically affects the economy via changes in credit conditions and housing demand. Next, we provide intuitive graphical analysis to illustrate how the emergence of rental markets and housing investors may alter this channel. Finally, we present the model and its results, demonstrating the new mechanisms through which monetary policy operates in the presence of a more prominent rental sector and active investor participation.

5.1. The Classic Transmission Channel

The housing market has traditionally played a key role in the monetary policy transmission mechanism, which is the process through which central banks influence economic activity, inflation, and financial conditions by adjusting interest rates or using other monetary policy tools.

The classic view of housing in the transmission channel for monetary policy was formalized by Iacoviello 2005 and focuses on the cost of credit and the prices of real estate owned by households. That is, when the central bank lowers interest rates, it becomes cheaper to borrow money, including mortgages. Lower mortgage rates stimulate both consumption by those households, who now pay less on their mortgages, and demand from potential buyers in the real estate market. This, in turn, generates price increases and wealth effects. That is, when house prices rise, homeowners are wealthier and more secure in their financial situation. This typically leads to increased consumer spending. Furthermore, rising house prices allow homeowners to obtain more credit using those properties as collateral, which provides an additional stimulus to consumption.

It should also be noted that real estate assets are a key component of the financial system. The value of the real estate market influences the balance sheets of banks and financial institutions, which, in turn, affects their willingness to lend. When the real estate market is strong, banks are more likely to provide credit to borrowers, making it easier to finance housing and other purchases. Conversely, if monetary policy leads to a fall in housing prices or lower demand for loans, banks suffer a negative impact on their balance sheets. This leads to tightening lending standards, which can have broader consequences for the availability of credit in other sectors of the economy.

In summary, according to traditional theories, the housing market has traditionally played a fundamental role in the effectiveness of monetary policy through three related channels: 1) credit markets, which affect the consumption of households with outstanding debt balances and those considering borrowing; 2) housing prices, which affect the wealth of homeowners and their ability to obtain credit; and 3) via bank balance sheets, which affect the supply of credit. However, these mechanisms weaken when many households cease to own homes and when home purchases are concentrated among investors who do not use credit. In this situation a new channel emerges with rental markets and housing investors at the core. Next we discuss this new channel.

5.2. Intuition for the New Rental Channel

We start by providing intuition on how the rental market affects the transmission of monetary policy to rents, house prices, homeownership, and ultimately consumption. Then we will confirm the insights using a full HANK model with rental markets and housing investors.

We use a simple supply and demand diagram to illustrate the core mechanisms at play. In particular, we emphasize the role of the elasticity of supply between the rental and owner-occupied housing markets. This elasticity reflects how easily housing units can be reallocated between the two segments, which in turn depends on the behavior of investors who buy or sell properties to shift them from one market to the other. The responsiveness of this reallocation process is central to understanding how shocks—such as changes in interest rates—propagate through the housing market and ultimately influence aggregate outcomes.

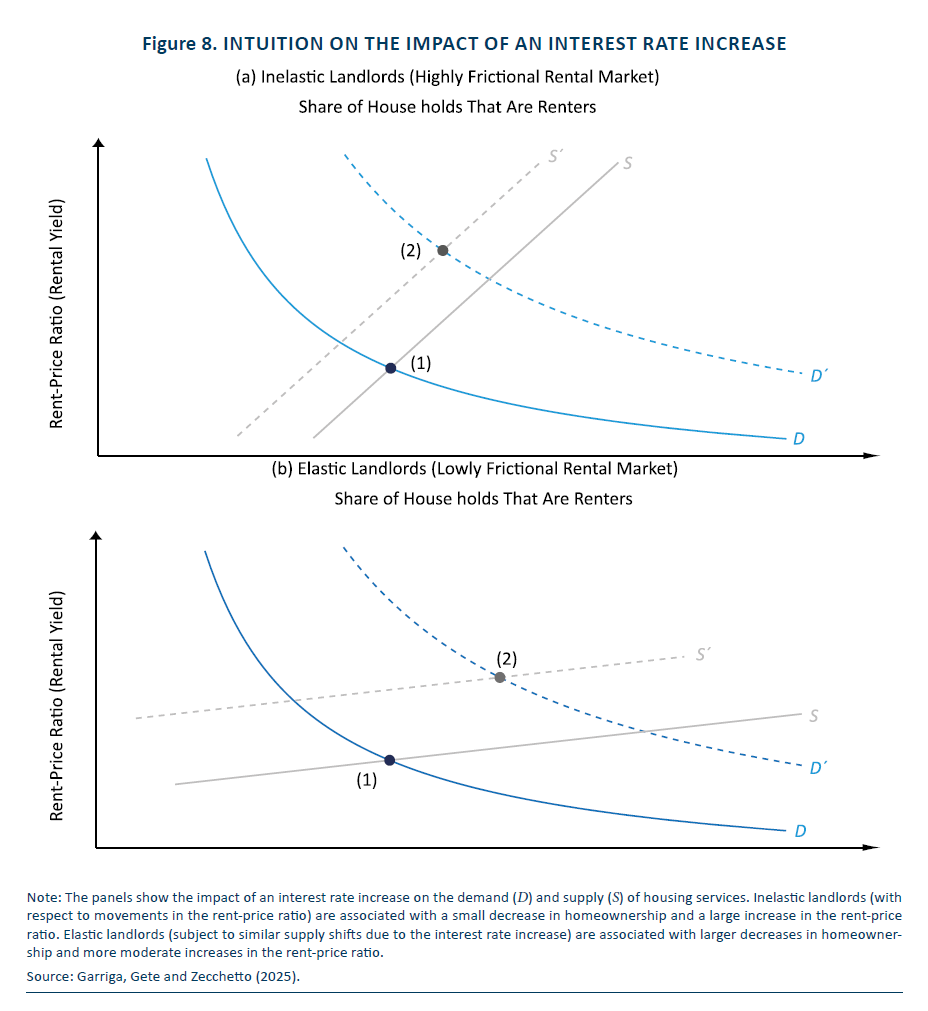

In Figure 8, the horizontal axis plots the share of households that are renters (i.e., one minus the homeownership rate), while the vertical axis plots the rent-price ratio, or rental yield. These axes represent the relative quantity and relative price of rental versus owner-occupied housing, respectively. The demand curve for rental services (D) represents the schedule of rent-price ratios for owner-occupied versus rental housing. As the rent-price ratio increases, fewer households prefer to rent—since owning becomes relatively more attractive—yielding a downward-sloping demand curve. The supply curve for rental services (S) represents the schedule at which landlords (or real estate investors) are willing to supply rental housing. As the rent-price ratio increases, rental investment becomes more attractive, so more landlords are willing to supply rental units, resulting in an upward-sloping supply curve.

Panel (a) illustrates the case of inelastic landlords, meaning that movements in the rent-price ratio are associated with only small changes in the quantity of rental housing supplied. The steep supply curve reflects frictions or slow adjustment in rental supply. Following a contractionary monetary policy shock that raises real interest rates, the demand curve shifts rightward (from D to D´), as higher mortgage costs make homeownership less affordable and increase the demand for rental housing at a given rent-price ratio. At the same time, the supply curve shifts leftward (from S to S´), due to higher mortgage costs that affect rental investment financing, as well as portfolio rebalancing away from real estate and toward alternative assets such as bonds. As a result, the equilibrium shifts from point (1) to point (2), with a modest decline in homeownership but a large increase in the rent-price ratio.

Panel (b) shows the case of elastic landlords, meaning that small movements in the rent-price ratio are associated with large changes in the quantity of rental housing supplied. In this case, a contractionary monetary shock—assuming a supply curve shift of similar magnitude as in panel (a)—leads the equilibrium to move from point (1) to point (2), but with a smaller increase in the rent-price ratio and a larger increase in the renter share (i.e., a larger decline in homeownership) compared to the inelastic landlord economy.

These differences in equilibrium adjustments across panels (a) and (b) have direct implications for aggregate consumption. In the inelastic landlord case, the sharp rise in the rent-price ratio results in higher rental costs, while the homeownership rate declines only modestly. If renters have higher marginal propensities to consume than owners (and if they represent a sizable share of the population), the increase in their housing expenditure translates into a stronger contraction in non-housing consumption. At the same time, landlords receive more rental income and may increase their consumption in response. However, if landlords have lower marginal propensities to consume—due to higher wealth and fewer liquidity constraints—and represent a smaller share of the population, the rise in their consumption would tend to only partially offset the decline among renters. In contrast, when landlord supply is elastic, the shift toward renting is larger but the increase in rental prices is smaller, which helps to cushion the fall in aggregate consumption. Taken together, this analysis suggests that the degree of supply responsiveness in the rental market plays a key role in shaping how monetary policy shocks propagate into consumption dynamics through housing tenure and affordability channels.

Finally, if the monetary authority targets an inflation index that includes rents, then the dynamics described above can further amplify the effects of monetary tightening. In particular, in the inelastic landlord case, the initial rise in rents contributes directly to measured inflation, potentially prompting the central bank to raise interest rates even further. This feedback loop can reinforce the contractionary effects on consumption. The responsiveness of rental supply thus not only shapes the initial transmission of policy but also affects the likelihood of amplification through the policy rule itself. These insights provide the intuition behind the “higher for longer” results, which we now formally demonstrate using a HANK model that incorporates rental markets and housing investors.

5.3. Model

It is a dynamic incomplete-markets general equilibrium model of household consumption and housing investment. The economy features a continuum of households, a representative final-good producer, a continuum of intermediate-good producers, a monetary authority, and a fiscal authority. Time is discrete and denoted by  . The Appendix contains all the equations.

. The Appendix contains all the equations.

Households are infinitely lived and face uninsurable idiosyncratic labor productivity shocks. A key innovation of the model is that households can trade housing both as a consumption good (owner-occupied housing) and as an investment asset (rental properties that generate income). Both types of housing are subject to adjustment costs that create illiquidity, and households can borrow against the value of their housing assets. A second innovation is the explicit inclusion of housing services in the overall consumption price index. That is, housing inflation can cause inflation, like in the data.

House prices, rents, the price of non-housing consumption, wages, inflation, and interest rates are all determined endogenously in equilibrium. Following standard practice in the literature, the model is written primarily in real terms, except for the Taylor rule, the Fisher equation, and the price-setting equations, which are specified in nominal terms.

5.4. The New Rental Channel

To illustrate the results, we analyze a one-time, unexpected contractionary monetary shock. We consider an experiment in which, at time  =0 , a mean-reverting quarterly shock to the Taylor rule (equation (15) in the Appendix) is introduced.5

=0 , a mean-reverting quarterly shock to the Taylor rule (equation (15) in the Appendix) is introduced.5

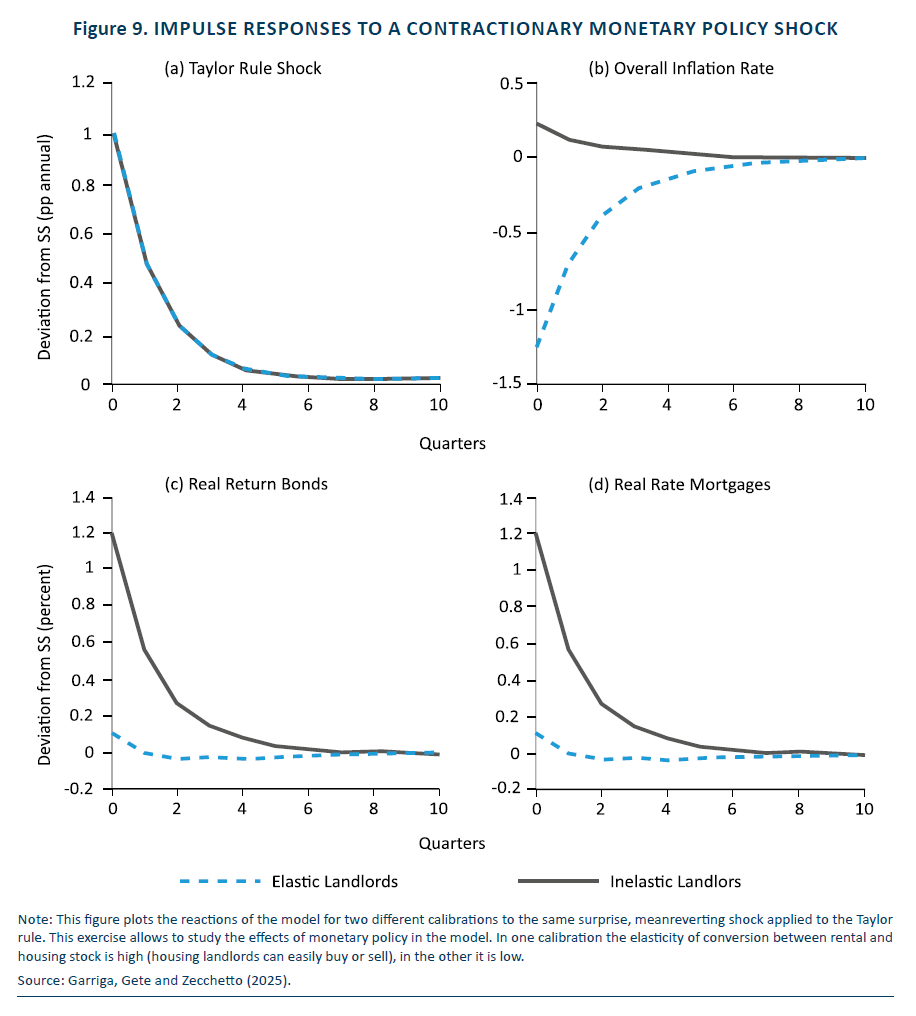

Figure 9 displays the exogenous monetary policy shock and the resulting dynamic responses for key aggregate variables: the overall inflation rate, the real return on bonds, and the real mortgage rate. Panel (a) shows that the monetary policy shock is identical across both model variants—defined by whether landlords have elastic or inelastic rental supply responses to changes in the rent-price ratio. The shock reaches its maximum value of 1 percentage point (annualized) on impact and then gradually declines toward zero. Panel (b) shows that in the economy with elastic landlords, overall inflation falls by about 1.2 percentage points (annualized) on impact, consistent with standard New Keynesian dynamics. In contrast, inflation in the inelastic landlord economy increases by approximately 0.3 percentage points. This striking divergence is driven by a sharp increase in both nominal and real rents in the inelastic case, which more than offsets the typical disinflationary effects from reduced non-housing demand.

Because rents enter directly into the consumer price index targeted by the central bank, the increase in rents causes measured inflation to remain persistently elevated in the inelastic landlord economy. As a result, the nominal interest rate also stays high for a more prolonged period. Consequently, as shown in panels (c) and (d), the real interest rates on both bonds and mortgages rise more sharply and remain elevated for longer in the inelastic landlord case. Specifically, the real return on bonds peaks around 1.2 percentage points above steady state in the inelastic case, compared to only about 0.2 percentage points in the elastic case. The results are similar for the real mortgage rate, since we assume a constant spread between mortgage and bond rates. These differences in real rates have important implications for real macroeconomic outcomes, which we discuss next.

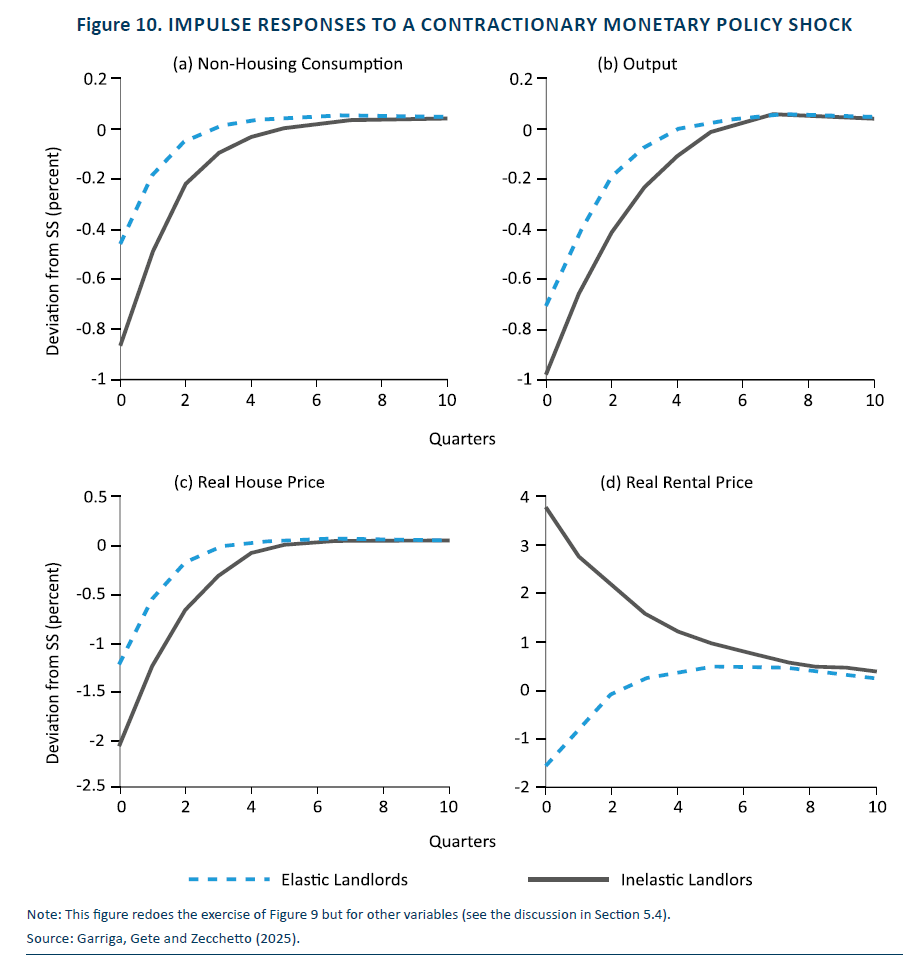

Figure 10 shows how the increase in real interest rates affects the real economy. Panel (a) illustrates a decline in non-housing consumption following the contractionary monetary shock. The decline is significantly larger in the economy with inelastic real estate investors, where non-housing consumption drops by about 0.8% on impact. In contrast, the decline is only around 0.4% in the elastic landlord case. This stronger consumption response can be traced to two novel channels linked to rental market dynamics.

First, higher mortgage rates discourage homeownership and shift demand toward rental markets, putting upward pressure on rents. When landlord supply is inelastic, rents increase disproportionately—as seen in panel (d), where real rental prices rise by nearly 4% on impact in the inelastic case, compared to a decline of about 1.5% in the elastic case. Because renters typically have higher marginal propensities to consume than the average household, this shift amplifies the contraction in aggregate consumption. Second, as discussed earlier, the increase in rents caused by the monetary shock raises measured inflation and keeps it persistently elevated. In response, the monetary authority maintains higher nominal interest rates for longer, resulting in a larger and more prolonged increase in real interest rates.

As a result, tight monetary policy may generate stronger real effects than predicted by standard HANK models that abstract from rental markets. Panel (b) confirms this, showing that output declines by nearly 1% in the inelastic case, compared to about 0.6% with elastic landlords. Since output is demand-determined in the presence of nominal rigidities, these differences reflect the stronger contraction in aggregate demand—particularly consumption—when rental supply is inelastic.

Panel (c) shows that real house prices fall more steeply in the inelastic economy—by about 2% on impact—compared to a smaller decline of 1.25% in the elastic case, where stronger investor demand helps cushion the price decline. The sharper drop in house prices further tightens financial conditions, particularly for leveraged households, who face negative wealth effects and tighter borrowing constraints. Since these households tend to have high marginal propensities to consume, this well-known transmission channel—when combined with inelastic landlord supply—reinforces the aggregate consumption decline.

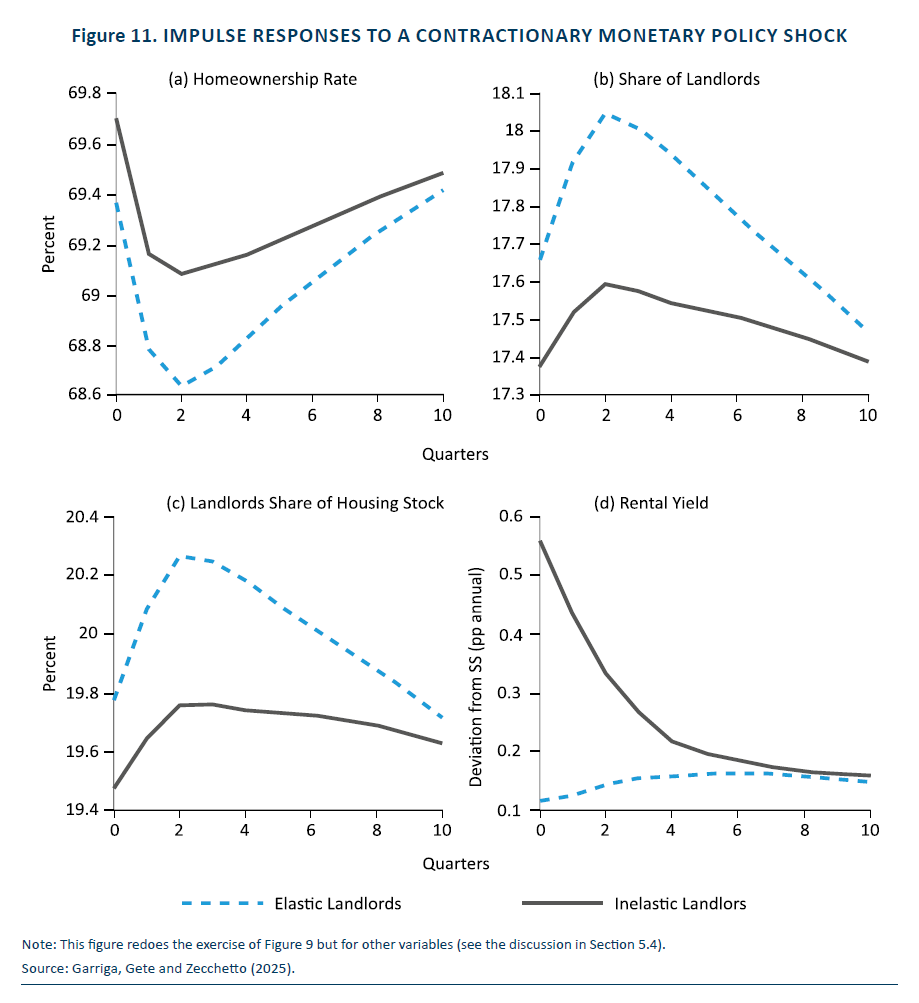

Figure 11 explores the implications of monetary tightening on housing market composition and rental returns. Panel (a) shows that the homeownership rate declines less in the economy with inelastic landlords, falling by about 0.6 percentage points relative to steady state. In contrast, the decline is nearly twice as large—about 1.2 percentage points—when landlord supply is elastic. This larger drop reflects the more aggressive expansion of rental housing by elastic landlords, which leads to a greater reallocation of households from ownership to renting, consistent with the model intuition discussed above.

Panels (b) and (c) in Figure 11 show the corresponding responses on the landlord side. Both the share of households acting as landlords and the share of the housing stock they hold rise more rapidly in the elastic case, reflecting their greater willingness and ability to expand rental supply. Rental yields spike by nearly 0.6 percentage points in the inelastic case—almost three times the increase observed under elastic supply. These elevated rental returns are needed to incentivize inelastic landlords to accommodate the surge in rental demand, in line with the economic mechanisms highlighted earlier.

In conclusion, the analysis reveals that the elasticity of rental housing supply plays a pivotal role in shaping the macroeconomic effects of monetary policy. A one-time contractionary monetary shock produces markedly different outcomes depending on whether landlords can adjust rental supply in response to changing economic conditions. When landlord supply is inelastic, the shock leads to an unexpected rise in inflation due to surging rents, which in turn forces the central bank to maintain higher nominal and real interest rates for an extended period—capturing the «higher for longer» dynamic. These elevated rates intensify the contraction in non-housing consumption, amplify the decline in output, and deepen the fall in house prices through stronger wealth and credit channel effects. The model also shows that housing market composition adjusts differently across regimes: elastic landlords respond by expanding rental supply and acquiring a larger share of the housing stock, whereas inelastic landlords restrict adjustment, resulting in higher rental yields and limited changes in ownership patterns. Overall, the findings highlight that incorporating rental markets and investor behavior into models of monetary policy allow to uncover novel transmission mechanisms of monetary policy that are masked in more traditional frameworks.

6. Conclusions

This paper shows that, in Spain, the aftermath of the financial crisis has been marked by a sharp decline in housing ownership among young households, while older households have significantly expanded their property holdings. This novel pattern is not unique to Spain and appears to hold across many European countries. The shift is driven by a combination of declining income and tighter credit conditions for younger households, alongside a search-for-yield behavior among older, wealthier investors. In parallel, Spain has seen a dramatic increase in the share of fixed-rate mortgages among new loans.

What are the implications of these structural changes for the transmission of monetary policy? While it is well-established that a decline in variable-rate mortgages weakens the effectiveness of monetary policy, the role of rental markets remains relatively unexplored. This paper contributes to filling that gap by incorporating rental markets and housing investors into a Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian (HANK) model. In doing so, we uncover new transmission channels. For example, when monetary policy tightens, rents may rise due to constrained housing supply, leading to inflationary pressures through the shelter component of the consumer price index. This dynamic can generate counterintuitive outcomes in which restrictive monetary policy contributes to higher inflation. Moreover, because tenants typically have higher marginal propensities to consume, increases in rent can amplify the contractionary effects on aggregate demand—implying that tight monetary policy may have stronger real effects than predicted by standard HANK models.

Housing investors play a key role in this framework by determining the elasticity of housing supply between the ownership and rental markets. This introduces a fundamentally different mechanism from the classical transmission channels of monetary policy through housing, which focus on mortgage debt, household wealth effects, and foreclosures. Future work should further explore the elasticity of conversion between rental and ownership housing, as well as the spread between rental yields and returns on safe assets—two variables that prove central to understanding how monetary policy affects modern housing markets and, by extension, the broader economy.

Referencias

Carbo, S., and Rodriguez, F. (2021).The Spanish housing market post COVID-19. SEFO, Vol.10(4). In: FUNCAS Sefo 10.4 (2021).

Carbo, S., and Rodriguez, F. (2022).La reactivación del mercado hipotecario español. Cuadernos de Información Económica, 287, 41–46.

Daniel, K., Garlappi,L., and Xiao, K (2021).Monetary policy and reaching for income. The Journal of Finance, 76(2), 1145–1193.

De Stefani, A. (2021). House price history, biased expectations, and credit cycles: The role of housing investors. Real Estate Economics, 49(4), 1238–1266.

Garriga, C., Gete, P., and Tsouderou, A. (2023). The economic effects of real estate investors. Real Estate Economics, 51(3), 655–685.

Garriga, C., Gete, P., and Zecchetto, F. (2025). Real Estate Investors, Rental Markets, and Monetary Policy.

Garriga, C., Kydland, F. E., and Sustek, R. (2017).Mortgages and monetary policy. The Review of Financial Studies, 30(10), 3337–3375.

Garriga, C., Manuelli, R., and Peralta-Alva, A. (2019). “A macroeconomic model of price swings in the housing market. American Economic Review 109(6), 2036–2072.

Iacoviello, M. (2005). House Prices, Borrowing Constraints, and Monetary Policy in the Business Cycle. The American Economic Review, 95.95 (3), 739–764.

Piazzesi, M., and Schneider, M. (2016). Housing and Macroeconomics. In Handbook of Macroeconomics. Vol. 2. (1547-1640).Elsevier.

Pica, S. (2021). Housing markets and the heterogeneous effects of monetary policy across the euro area. Available at SSRN 4060424.

Rubio, M. (2011). Fixed-and variable-rate mortgages, business cycles, and monetary policy. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 43(4), 657–688.

Torres, R. (2023). Increases in Euribor and potential impact on mortgages and the Spanish economy. SEFO, 12(2). 20

NOTAS

* IE University

** I am grateful to seminar participants at various institutions for their valuable comments, and I acknowledge the financial support of FUNCAS. This paper is based on joint work with my esteemed coauthors Carlos Garriga, Athena Tsouderou, and Franco Zecchetto. All views expressed are my own, and I take full responsibility for them. I thank Vicente Rojas for excellent research assistance.

1 In related work, Daniel, et al., (2021) show reach for income among U.S. equity investors. De Stefani (2021) documents that the investment attitude towards housing increased significantly among the wealthy U.S. population following the financial crisis. Garriga, et al., (2023) study the surge of local investors in the U.S. after the global financial crisis.

2 A HANK model, which stands for Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian model, is a framework in macroeconomics that incorporates differences across households into a standard New Keynesian structure. Unlike traditional models that assume a representative agent, HANK models account for household heterogeneity in terms of income, wealth, and sensitivity to economic shocks. We do not model banks explicitly, but instead use a lending rule that—consistent with standard practice in the literature—generates a positive correlation between credit availability and housing prices.

3 Carbo-Valverde and Rodriguez-Fernandez (2022) were among the first to point-out this structural transformation.

4 Surveying different households reduces the serial correlation of the variables between survey waves.

5 Model details are in the Appendix. The shock has an initial magnitude of ϵ0 = 0.25% (equivalent to 1% annually) and decays at rate ς, so that ϵt = exp(−ςt)ϵ0. We set ς = 0.75, which corresponds to a quarterly autocorrelation of exp(−ς) = 0.47.

APPENDIX