The EU recovery fund: strengths and limitations

Fecha: julio 2020

Miguel Carrión Álvarez

The recovery fund dominated the agenda of last weekend’s European Council, which also agreed on the EU’s 2021-2027 multiannual financial framework or “EU budget”. The rationale for the recovery fund is that Covid-19 has caused a sharp and deep recession. The private sector has suffered serious economic damage despite massive government support. And this support has caused high public deficits and an increase in public debt, which will make it harder for governments to continue to support the recoveries of their economies. Therefore, a European recovery fund that doesn’t burden member states with more debt is necessary.

Left to their own devices, member states would continue to diverge economically, because countries’ responses so far correlate with their fiscal space rather than with the impact of the pandemic. The European Commission suspended the fiscal rules this year on account of the health emergency. But the concern remains that the restoration of the fiscal rules as early as next year may lead to a contraction of public investment, at a time when private investment has collapsed and is not expected to recover. Keeping up aggregate investment will be critical in preventing a lasting reduction of European economic capacity, which would be associated with a durable increase in unemployment.

The July Council summit agreed a budget proposal of about the same size as originally proposed by Council President Charles Michel, but with substantially different composition of the recovery fund (1). The agreement includes a €750bn recovery fund as proposed originally by the Commission, to be disbursed over three years in 2021-23. However, several of the contributions to European Commission programmes have been cut substantially in negotiations, as several governments opposed large transfers from the recovery fund.

As we have noted, one function of the recovery fund is to reduce the future debt burden of the member states. Only the transfers component of the fund achieves this. The loans component may improve things marginally, by reducing member states’ debt-service costs relative to bond market financing, but it will still add to the public debt stock. For this reason, the operative size of the recovery fund is not the whole €750bn but the €390bn of the grants component. As this is to be disbursed over three years, the annual grant amount is €130bn on average.

The public debate on both the recovery fund and the EU budget seems to have revolved around haggling on the amounts of money to be borrowed, spent or lent, but without reference to the EU’s actual spending and investment needs. Some of the components of the recovery fund that would have impacted investment most directly have been the first to be cut. Sustaining net investment should have been the primary concern around the Council table, but it wasn’t.

1. The impact of Covid-19 on investment

The Commission’s best estimate is that eurozone private investment will contract by 3% of GDP this year, and not recover or be made up by public investment in the years to come. For comparison with the recovery fund, 3% of 2019 eurozone GDP is €360bn per year.

By now, it is looking like the milder baseline scenario in the European Commission’s spring forecast might be realised. This foresees EU real GDP dropping by 7.5% in 2020 (2). Member states’ stability and convergence plans are significantly more optimistic, anticipating a 6.2% real GDP drop on average (3).

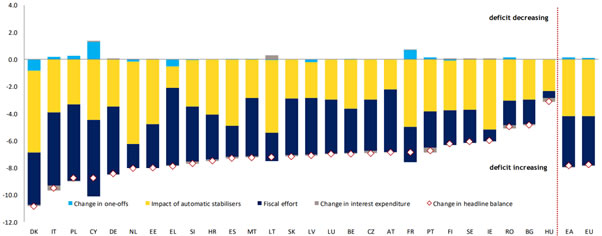

Accordingly, the aggregate government deficit-to-GDP ratio is projected to increase by almost 8 percentage points. Of this increase, about 40 percent comes from discretionary fiscal spending measures adopted until the late-April cut-off date of the Commission’s spring forecast, and the rest from automatic stabilisers and discretionary tax measures (see figure 1). These discretionary fiscal measures are mostly in the form of income transfers, with some spending on health care costs.

Figure 1: change in budget balance from 2019 to 2020 (DG EcFin)

Figure 1 shows changes in the public budget balance between 2019 and 2020. This is broken down into: discretionary fiscal effort, mostly on the expenditure side; changes in interest expenditure; changes in one-offs; and the impact of automatic stabilizers, which includes revenue windfalls or shortfalls not associated to the business cycle. The fiscal measures taken in response to the Covid-19 outbreak in 2020 are not treated as one-offs, so presumably they count toward the fiscal effort if they affect expenditure, and toward automatic stabilisers if they affect revenue.

This fiscal expansion will only party compensate for the loss of income of the private sector in 2020. The staff working document accompanying the European Commission’s spring forecast included estimates of the impact of the recession on private sector solvency and investment (2). The way an overall drop in GDP works its way through the economy is, first, a reduction in firms’ revenue. This then results in layoffs to cut wage costs. In this crisis, governments have subsidised wages through short-work schemes in order to reduce the loss of employment. They have also provided liquidity to firms through tax deferrals and credit guarantees. But these credit guarantees were largely for working capital, not for investment.

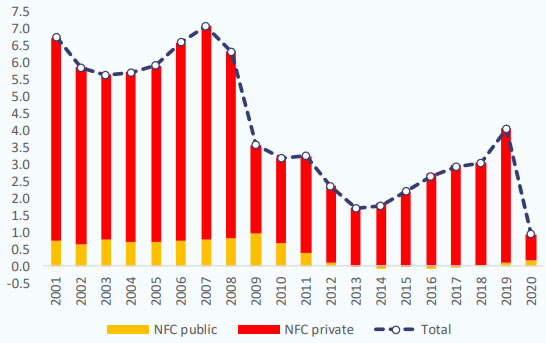

Lower profits result in lower tax liabilities, which contribute to the automatic stabiliser component of the fiscal stimulus. But, ultimately, the drop in profits results in a loss of private investment. The Commission’s forecast is that private investment is likely to fall by 3% of GDP, to almost zero as shown in figure 2. This shows net investment, that is gross investment net of the cost of repairing the loss of existing capital stock from normal wear and tear.

Figure 2: eurozone net private and public investment (DG EcFin)

Figure 2 highlights not just the failure of public investment in the eurozone to make up for a steep drop in private investment after 2008 due to the global financial crisis. There is also the fact that net public investment shrank in the eurozone as a result of the subsequent government debt crisis, and has remained essentially at zero since.

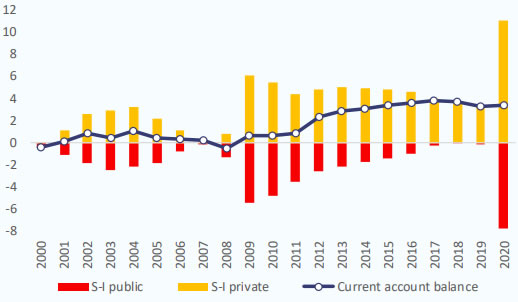

The modest recovery of private investment since the recovery started in 2013 correlates with increased saving by the private sector even as the public sector reduced its deficit. The result was that excess private saving could not be absorbed by government borrowing, and had to be directed to foreign assets. This is called a savings glut, and can be seen in the rise of the eurozone’s current account surplus since 2012, as shown in figure 3.

The Commission’s overview of the stability and convergence plans suggests increasing public investment to reduce the savings glut (3). This would entail deficit spending funded by borrowing from the foreign sector. Given the size of the current account surplus, up to 3-4% of GDP worth of investment could be funded in this way. This is, however, a structural change that would take a few years to complete. It would even be possible to do this while improving the net international investment position of the eurozone, so long as the foreign borrowing in nominal terms is less than nominal GDP growth.

Figure 3: eurozone sectoral excess saving over investment (DG EcFin)

2. Public equity injections would have been money well spent

In sum, private firms will be responding to their loss of revenue from the pandemic by conserving capital and thus cutting down on investment this year. The reason private investment is not expected to recover is that the weaker firms will also experience a liquidity shortfall this year. According to the European Commission, total losses to private companies in 2020 could add up to €720bn, or over 5% of the EU’s 2019 GDP. This could translate into around 200,000 companies, which employ about 30m people, suffering a liquidity shortfall between €350bn and €500bn due to having insufficient capital and liquidity buffers (2). These firms may not be able to access private credit even under the existing government guarantees, precisely because they are the ones with a weaker financial position to begin with. The ensuing solvency crisis, if not mitigated by a public equity injection, will be a drag on private investment in the following years.

The recession is therefore expected to result in a loss of investment. Compared to the autumn 2019 forecast, the Commission’s spring forecast implies a loss of private investment by €831bn in 2020 and 2021. This is just under 3% of 2019 GDP for two years, in line with chart 2 above.

What this means is that a public equity injection now would save a substantial amount of public investment in the future. The argument goes like this. Private firms are expected to have a capital shortfall of the order of €400bn this year. If this is not repaired, the effect of this will be a loss of private investment of about the same amount this year and next, and perhaps every year thereafter. For aggregate investment to be sustained, deficit-funded public investment, also of the order of €400bn, would be necessary.

Alternatively, the public sector could inject capital into firms that would be viable in principle but find themselves under water due to Covid-19. Doing this now would allow these firms to resume investment by themselves in the following years, as their solvency would have been repaired. The approximate equality of the estimated capital shortfall and the estimated drop in annual investment suggests that every euro of public money spent this year on private-sector equity support could translate into one additional euro of private investment, and thus save one euro of compensatory public investment every year thereafter.

This must be why the European Commission included a Solvency Support Instrument within its proposed recovery fund. This would have been structured as a guarantee fund, managed by the European Investment Bank in the mould of the Juncker Plan (4):

“A new Solvency Support Instrument will mobilise private resources to provide urgent support to otherwise healthy companies. Investment will be channelled to companies in the sectors, regions and countries most affected. This will help to level-up the playing field for those Member States who are less able to support through State aid. It can be operational from 2020 and will have a budget of €31 billion, aiming to unlock more than €300 billion in solvency support. Guidelines will be developed to help align investments towards EU priorities.”

We have criticised the structured finance underlying these kinds of leveraged guarantees, particularly when the goal is to fund equity (5). There we argued that a multiplier of close to 10 times is borderline-plausible when the aim is to support credit with an equity-like guarantee, but it is far-fetched when the end goal is to fund equity. In this particular case the aim is to provide liquidity to prevent a capital shortfall, so the proposed guarantee fund seems to try to leverage equity into more equity. Be that as it may, any configuration of a €31bn equity fund would have gone a long way towards increasing private investment in the future. It was therefore dismaying that this was one of the first components of the proposed recovery fund that was cut in its entirety to satisfy sceptical members of the European Council members.

3. The eurozone’s tight fiscal stance

The conclusion is, therefore, that the drop in private investment in 2020 is likely to be lasting, and the expectation is that public investment will not rise to make up for the expected loss of private investment, leading to a long-term loss of economic potential.

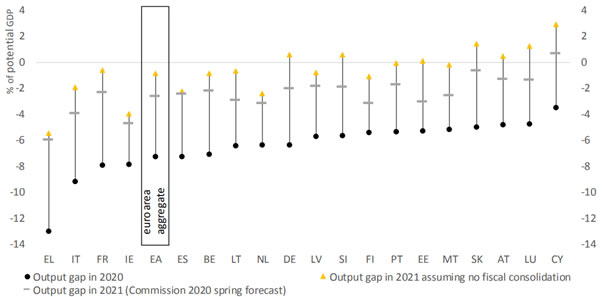

The European Fiscal Board estimates, assuming discretionary fiscal support ends in 2020, that the eurozone’s fiscal stance in 2021 may be too tight by at least 2% of GDP in the absence of policy change (6), as shown in figure 4. This is the amount by which the reduction in the primary deficit will be excessive. That is the eurozone’s fiscal stance in 2021 is expected to too tight by 2%, in the direction of contributing pro-cyclically to contracting the economy. The primary deficit would have to be 2% larger than expected in 2021 in order for the eurozone’s fiscal stance to contribute to economic growth recovering towards its potential.

The member states are still in time to correct this in their draft budgetary plans for 2021, due this autumn. However, political pressure is intense for national governments to return to a debt-reduction path compatible with the fiscal compact. The EU is on track to repeating the policy mistake of the global financial crisis. In 2010, the eurozone engaged in premature fiscal contraction in 2010 in reaction to the high public deficits incurred in 2009.

For 2021, the Commission’s spring forecast foresees that the eurozone economy will still be operating substantially below capacity, and the European fiscal board estimates that fiscal consolidation may contribute about two percentage points of GDP to the output gap (6). This is shown in figure 5. Budgetary tightening threatens to be a huge drag on the eurozone economy as it attempts to recover from the deep and sharp recession caused by Covid-19.

Figure 5:eurozone expected 2021 fiscal stance (European Fiscal Board)

In figure 5, the vertical bars show the effect of a reduction of the output gap by 50-100% from 2020 to 2021. This assumes a fiscal multiplier of 0.8, that is, that each additional euro of public deficit translates into a €0.8 GDP increase. Fiscal consolidation is assumed to bring the debt-to-GDP ratio to 60% by 2034, which is perhaps too stringent as the requirement in the fiscal compact is to reduce the excess over 60% by 1/20 per year. The forecast does not include member states’ draft budgetary plans for 2021, nor recently announced stimulus measures.

It is thus easy to justify the need for a deficit-financed increase in EU public investment by at least 2% of GDP over the medium term. Nevertheless, the European Council struggled to agree a recovery fund with a grants component adding up to less than 1% of GDP each year over three years.

Figure 5 also helps explain why the loans component of the recovery fund is much less effective than the grants component in this context. If the European Commission borrows in the financial markets to lend to the member states, the net effect on the stock of debt is just as if the member states had borrowed from the market. The European union just stands as an intermediary between member states and the market, but the fiscal stance of the member states has not changed.

On the other hand, European Union grants increase public sector spending, thus closing the output gap, without increasing member states’ deficits. The grants component of the recovery fund is €390bn over three years, which is under 1% of the EU’s 2019 GDP. This is less than the expected 2% by which the primary deficit is expected to be too tight next year.

4. The problem of chronic public under-investment

As shown in figure 2 above, net public investment in the eurozone was close to 1% of GDP until 2009, at which point it started declining to near zero where it’s been since 2012. Net public investment of 1% is consistent with a stock of public capital of about 50% of GDP in the short term and increasing in the long term, according to the DG EcFin (3). By this measure, the eurozone’s public sector is currently under-investing by about €100bn a year, or about 0.7% of GDP, and failing to keep the size of the public capital stock as a multiple of GDP. Meantime, as shown in figure 3, the private sector will continue to invest nearly 4% of GDP in foreign assets.

The staff working document accompanying the European Commission’s #NextGenerationEU budget proposals also estimates at €20bn a year the additional investment needs revealed by the crisis (2). These would go towards improving the strategic autonomy of the EU from global supply chains that might be compromised by future crises. This investment relates to: strategic sectors not necessarily related to the pandemic, such as digital infrastructures or defence and aerospace; enabling technologies and critical raw materials; and medical and pharmaceutical supplies.

Finally, even before the effect of the pandemic, meeting the EU’s policy goals requires additional investment of €595bn a year. This breaks down into €470bn to meet the EU’s climate and environmental policy goals by 2030, and €125bn for the digital transformation of the EU economy. The €470bn for climate and the environment involve €240bn for the climate and energy targets, as well as €100bn for transport infrastructure and €130bn for environmental goals.

In addition to all this, the Covid-19 crisis has highlighted the need for strengthening the EU’s public health care system as well as the social safety net generally. The staff working document estimates additional social infrastructure investment needs of €192bn a year.

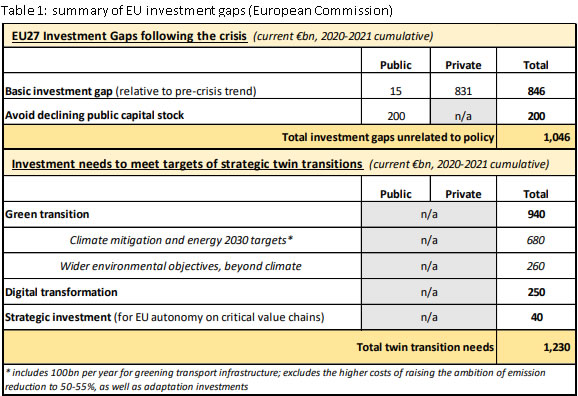

All of these investment needs are summarised in table 1. It should be noted that the investment shortfall associated to the pre-existing EU strategic goals, is for this year and next only. This is over €600bn a year on average, or 4-5% of EU GDP, and one should assume an investment shortfall of approximately that size for every year of the next decade until 2030.

From this table, the EU’s multiannual financial framework and recovery fund proposals fall well short of meeting these investment needs, unless one assumes as the Commission does that investment is able to be leveraged several-fold through EIB guarantee funds. The recovery fund amounts to €250bn per year, in loans and grants, which is about half of the investment shortfall due to Covid-19 this year and next. The EU budget, of a bit over 1 trillion euros over seven years, is less than EU’s strategic investment needs for the next two years.

Critics of the recovery fund within the Council, who typically also rejected leveraged investment schemes through the European Investment Bank, made no effort to argue that the above investment gaps were overstated, or that they can to be met by the private sector without public support. The reality is that, if these investment gaps are of the right order of magnitude, they will remain unfilled by the approved EU budget and recovery fund, which will seriously hamper the EU’s future economic potential and its wellbeing.

On the flip side, in so far as the recovery fund is directed towards environmental, sustainability, energy and climate goals, it contributes to reduce the pre-Covid-19 investment shortfall. So, the additional investment needed to meet these goals may be cut by nearly half with appropriate policy.

5. Summary and conclusion

At the end of May 2020, the European Commission presented its proposal for a recovery instrument called Next Generation EU (7), which would raise up to €750bn in the capital markets and channel the money through EU programmes. In his invitation letter to the European Council’s videoconference on 19th June 2020 (8), Council president Charles Michel asserted an emerging consensus on the need for the magnitude of the Covid-19 crisis response to be commensurate to the challenge. But, at the same time, he saw a need for further debate on the size and duration of the recovery plan, as well as on the size of the multiannual financial framework. Though the June videoconference was inconclusive, the European Council summit on July 17-21 reached an agreement on the recovery fund and the next EU budget.

Reports from the European Commission and one of its advisory bodies, the European Fiscal Board, painted a stark picture of the eurozone’s fiscal stance. One of the most robust predictions is that private investment will fall by 3% of GDP, that is about €360bn a year for the eurozone or €420bn for the EU as a whole, on the basis of 2019 GDP. The recovery fund, of €250bn a year over three years, falls well short of providing for that amount of investment.

One way to address the investment shortfall due to the pandemic would have been through what the Commission staff called equity repair (2). This is because, if the public sector redressed the impact of the recession on the solvency of private companies, these could resume investing on their own in future years. Government support in this crisis so far has aimed to support firms’ liquidity, subsidise wages, and defer taxes. But this still does not address the effect of the recession on investment and solvency of private firms. As a result, public investment needs to make up for lost private investment will be correspondingly higher.

But the EU’s total investment shortfall is much greater than this, adding up to between one and two trillion euros over just this year and next. This is because, to the effects of the Covid-19 crisis, one must add the pre-existing investment needs of the EU to meet its climate and sustainability goals. These amount to well over a trillion euros over this year and next, which is more than the size of the whole EU budget for a seven-year period.

In sum, public investment in the Eurozone was already insufficient as a result of many years of fiscal retrenchment, leading to an erosion of the public capital stock as a fraction of GDP. As the EU was about to embark on an ambitious programme of investment to meet its 2030 climate and energy targets, the Covid-19 crisis came to perhaps double the EU’s investment needs. The European Council failed to acknowledge the size of these investment needs when discussing the recovery fund, arguing instead over the amount of EU grants that was politically acceptable. The Council ended up leaving the EU’s sizeable investment needs up to a private sector in the throes of a solvency crisis. In the long run, this may prove not to have been sound fiscal policy.

References

1. European Council. Special European Council, 17-21 July 2020. Meetings. [Online] 21 July 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/european-council/2020/07/17-21/.

2. European Commission. Identifying Europe's recovery needs. Press Corner. [Online] 27 May 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/assessment_of_economic_and_investment_needs.pdf.

3. Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. The 2020 Stability and Convergence Programmes: an Overview, with an Assessment of the Euro Area Fiscal Stance. European Commission. [Online] 6 July 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/2020-stability-and-convergence-programmes-overview-assessment-euro-area-fiscal-stance_en.

4. European Commission. Europe's moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation. Eur-Lex. [Online] 27 May 2020. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0456&from=EN.

5. Carrión Álvarez, Miguel and Torres, Ramón. Overcoming the Covid-19 crisis through credit guarantees: rationale and risks. Funcas Europe. [Online] 27 May 2020. https://www.funcas.es/funcaseurope/Overcoming-the-Covid-19-crisis-through-credit-guarantees-rationale-and-risks.

6. European Fiscal Board. Assessment of the fiscal stance appropriate for the euro area. European Commission. [Online] 1 July 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/assessment-fiscal-stance-appropriate-euro-area_en.

7. European Commission. Europe's moment: Repair and prepare for the next generation. Press Corner. [Online] 27 May 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_940.

8. Council of the European Union. Invitation letter by President Charles Michel to the members of the European Council ahead of their video conference on 19 June 2020. Press. [Online] 16 June 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/06/16/invitation-letter-by-president-charles-michel-to-the-members-of-the-european-council-ahead-of-their-video-conference-on-19-june-2020/.