Completing the banking union: the key role of the resolution backstop

Fecha: diciembre 2020

Miguel Carrión Álvarez, Funcas Europe

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic caused a significant delay on the EU’s banking union policy agenda (1). The German presidency, however, succeeded in closing at least one chapter in the second half of the year. At the Euro Summit on December 11, leaders endorsed the Eurogroup’s previous agreement on reform of the European Stability Mechanism (2). This includes the early introduction of an ESM backstop to the Single Resolution Fund (SRF). The main outstanding issues for the banking union are setting up a European Deposit Insurance Scheme; and liquidity in resolution, which addresses the possibility that a bank may emerge from a restructuring without sufficient access to market liquidity.

In June 2019, broad political agreement on ESM reform was achieved (3). Then in December, an agreement in principle was reached on the legal framework for the ESM to provide a backstop to the Single Resolution Fund (4). The decision has finally been made to proceed with signature and ratification, and to accelerate the timeline of the SRF backstop by nearly two years.

Originally, the plan was to introduce the backstop by the end of 2023, provided sufficient risk reduction in the banking system (5). Risk reduction is shorthand for the conditions necessary for all member states to accept the mutualisation inherent in the backstop. It is noteworthy that, despite recognising that the previously-agreed quantitative benchmarks for risk reduction have not been met, the Eurogroup finally agreed to introduce the resolution backstop by the start of 2022.

This purpose of this note is to look at the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the risk reduction targets that underpin the recent decision to introduce a resolution backstop.

The process of risk reduction for the common resolution backstop

In December 2018, the Eurogroup made early adoption of the resolution backstop conditional on banks increasing their loss-absorbing capital and asset quality uniformly across the banking union (6). The loss-absorbing capital requirement was phrased in terms of banks building up their minimum requirements for eligible liabilities (MREL), but without quantitative targets because MREL are set by the resolution authorities on a bank-by-bank basis. Asset quality was phrased in terms of non-performing loan reduction, with a target gross NPL ratio of 5% for all banks, and 2.5% net of provisions. Progress on these objectives is regularly assessed by the European Commission, European Central Bank, and ESM, in a risk-reduction report (7).

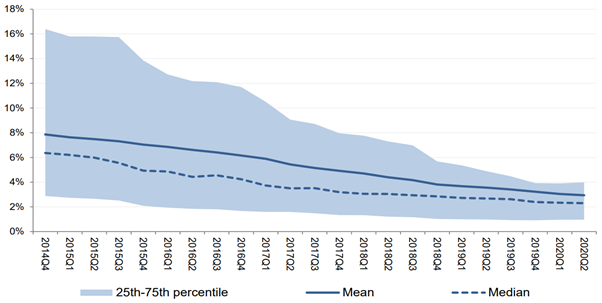

According to the institutions’ latest risk-reduction report, significant banks meet the NPL reduction targets on average since the turn of 2018, and more than 75% of all banks meet the targets since last year (figure 1).

Figure 1: evolution of gross NPL ratio in the banking union (source: EU institutions)

However, the worst-performing 25% of all banks have an average NPL ratio exceeding 10% on a gross basis, and 6% on a net basis. The trend is of steady reduction, though, except for a slight increase in the average gross NPL ratio of the worst-performing 25% of all banks in the second quarter of 2020, coinciding with the first wave of the pandemic.

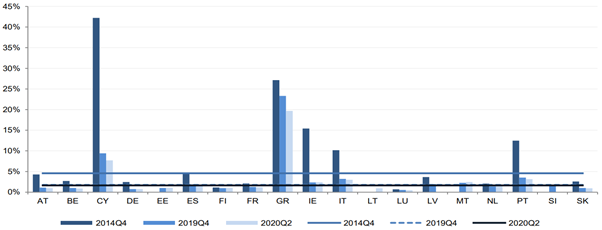

Figure 2: net NPL ratio by member state and banking-union average (source: EU institutions)

By countries, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, and Portugal are the ones that do not meet the targets on average. This is shown in figure 2.

The EU’s Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive allows failing banks to be recapitalised by the state, provided that at least 8% of liabilities and own funds have been written down (8). So that this bail-in tool does not cause undue stress, banks are required to accumulate bail-in-able liabilities in a sufficient amount. This minimum requirement for eligible liabilities (MREL) is set in individual banks’ resolution plans, as a fraction of the so-called total risk exposure amount (TREA) among other criteria.

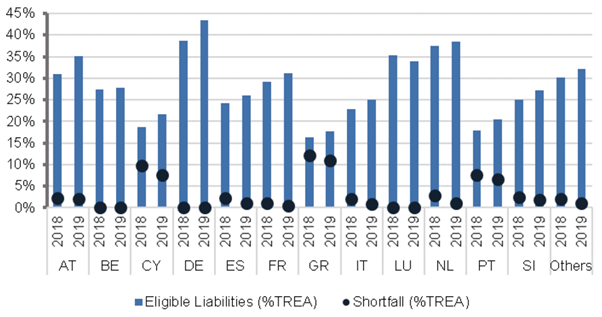

Figure 3: MREL shortfall by member state in 2018-2019 (source: EU Institutions)

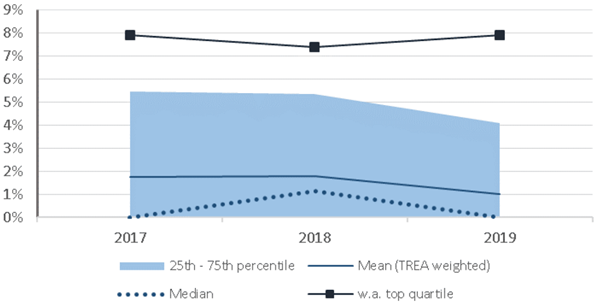

The institutions’ risk-reduction report focuses on the banks’ MREL shortfall as a fraction of their total risk exposure (7). Banks in Cyprus, Greece and Portugal were reported to have MREL shortfalls of between 5% and 15%, though these figures had improved during 2019 as seen in figure 3. On average, the MREL shortfall was 1% of TREA at the end of 2019, on a declining trend, though this trend was reversed in the first half of 2020 and the average shortfall increased to 2%. The best-performing 25% of all banks had no MREL shortfall at the end of 2019. On the other hand, the worst-performing 25% of all banks had an average MREL shortfall of about 8%, which had worsened in 2019 already as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: evolution of total MREL shortfall in the banking union (source: EU institutions)

The impact of Covid-19

The size of banks’ balance sheets increased significantly in the first half of 2020, coinciding with the first wave of the pandemic (7). According to the risk-reduction report, total liabilities and own funds rose by nearly 10%. Because of the contribution of the leverage ratio to MREL targets, this was responsible for the observed increase in the MREL shortfall.

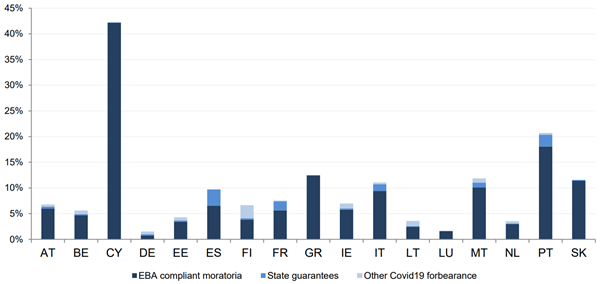

Covid-19 credit support measures have taken the form mostly of payment moratoria, affecting over 5% of all loans, followed by government loan guarantees affecting over 1%, and a marginal contribution from other measures. Portugal and especially Cyprus have a significantly higher proportion of loans under moratorium. This is 15-20% in Portugal compared with about 10% for the next tier of member states. In Cyprus, more than 40% of all loans are benefitting from loan moratoria. This is shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Covid-19 fraction of total loans by member state (source: EU institutions)

So long as loan moratoria comply with standards set by the European Banking Association, the affected loans need not be classified as unlikely to be repaid (9). But loans under loan moratoria are at a significantly higher risk of becoming non-performing the longer-lasting the economic crisis associated to the pandemic. Noting that Cyprus and Portugal are two countries with both excess NPL ratios and MREL shortfalls, the high use of Covid-19 guarantees in these two countries should be a cause for concern

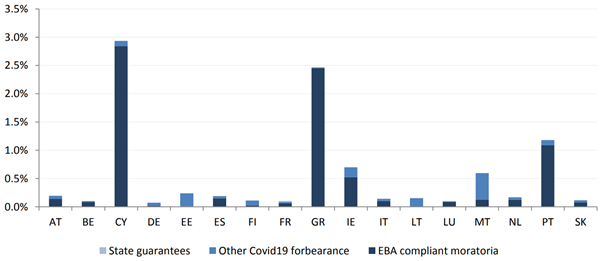

Figure 6: Covid19 NPLs (source: EU institutions)

Despite the leniency on classification of loans under Covid-19 credit support measures, it is still possible that some of them will have become nonperforming this year. In a few countries including, but not limited to, Cyprus and Portugal, loans under guarantee are already significant contributors to NPL ratios. This is shown in figure 6. In Greece, Covid-19 loans contribute 2.5 percentage points to the NPL ratio. Considering the gross target of 5%, this is a very significant effect. In Cyprus, which has a much higher proportion of Covid-19 loans, these contribute nearly 3 percentage points to the NPL ratio. For Portugal, the contribution is 1 percentage point, much smaller but still significant. In Ireland and Malta, Covid-19 loans contribute 0.5 percentage points to the non-performing loan ratio. This is not an excessive amount, but it is still significantly higher than in the rest of the member states. It is mostly due to loan moratoria in the case of Ireland and to government guarantees in the case of Malta.

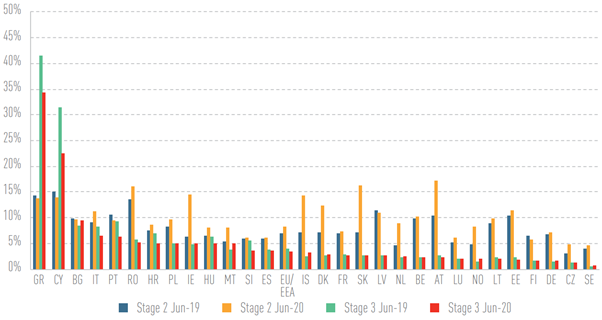

A recent risk assessment by the European Banking Authority also shows a significant worsening of credit quality in some core Eurozone countries (10). This is shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: distribution of Stage 2-3 loans in June 2019 and June 2020 (source: EBA)

In this chart, stage-3 refers to loans unlikely to be repaid. Stage-2 loans are those that are still performing but whose credit quality has deteriorated since the loan was granted.

Figure 7 shows the change in the proportion of Stage-2 and Stage-3 loans in the year to June 2020. Stage-2 loans increased significantly in Austria, from about 10% to about 17%; and the Netherlands, with an increase from about 5% to about 9%.

Conclusion: the closing window of opportunity

The conclusion from the above is that Covid-19 is already having a visible negative effect on progress towards the risk-reduction targets that the Eurogroup had previously agreed for the introduction of the resolution backstop. It is plausible that this negative impact will become significant in the coming months or years.

As early as June of next year, there may be evidence of backsliding on the risk-reduction targets. Yet, it is possible that the economic crisis brough about by the Covid-19 pandemic will not cause a steep rise in non-performing loans before the start of 2022. By then, the resolution backstop will be in place to deal with any bank failures that may occur. This is thanks to the decision to accelerate the introduction of the backstop.

It is therefore to be celebrated that the Eurogroup took such a decision, thus seizing the occasion to focus on the risk-reduction progress made so far. This highlights an improved climate of goodwill among member states on account of the pandemic affecting them all.

References

1. Carrión Álvarez, Miguel. The state of play on Banking Union. Funcas. [Online] October 2020. https://www.funcas.es/articulos/the-state-of-play-on-banking-union/.

2. European Council. Euro Summit. Meetings. [Online] 11 December 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/euro-summit/2020/12/11/.

3. Council of the European Union. Economic and Monetary Union: Eurogroup agrees term sheet on euro-area budgetary instrument and revised ESM treaty. Press. [Online] 15 June 2019. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/06/15/economic-and-monetary-union-eurogroup-agrees-term-sheet-on-euro-area-budgetary-instrument-and-revised-esm-treaty/.

4. —. Eurogroup. Meetings. [Online] 4 December 2019. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/eurogroup/2019/12/04/.

5. —. Statement of the Eurogroup in inclusive format on the ESM reform and the early introduction of the backstop to the Single Resolution Fund. Press. [Online] 30 November 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/11/30/statement-of-the-eurogroup-in-inclusive-format-on-the-esm-reform-and-the-early-introduction-of-the-backstop-to-the-single-resolution-fund/.

6. —. Eurogroup report to Leaders on EMU deepening. Press. [Online] 4 December 2018. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/12/04/eurogroup-report-to-leaders-on-emu-deepening/.

7. European Commission, European Central Bank and Single Resolution Board. Monitoring report on risk reduction indicators. Council of the European Union. [Online] November 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/46978/joint-risk-reduction-monitoring-report-to-eg_november-2020_for-publication.pdf.

8. European Union. Consolidated text: Directive 2014/59/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 establishing a framework for the recovery and resolution of credit institutions and investment firms. Eur-Lex home. [Online] 07 01 2020. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02014L0059-20200107.

9. European Banking Authority. The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria. News & press. [Online] 2 December 2020. https://eba.europa.eu/eba-reactivates-its-guidelines-legislative-and-non-legislative-moratoria.

10. —. EBA confirms banks’ solid capital and liquidity positions but warns about asset quality prospects and structurally low profitability. News & Press. [Online] 11 December 2020. https://eba.europa.eu/eba-confirms-banks%E2%80%99-solid-capital-and-liquidity-positions-warns-about-asset-quality-prospects-and.