What the absorption of structural funds says about the EU recovery plan

Fecha: noviembre 2020

Miguel Carrión Álvarez, Funcas Europe

As part of the debate on the impact of the EU recovery plan, a lot of emphasis has been put on the low absorption rate of EU cohesion funds (1). Six months before the end of the 2014-2020 budget period, only 47% of the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) had been disbursed (2). This, however, is misleading. EU budget commitments may be spent up to three years after being approved, and some money is disbursed even later than that. About 97% of the funds budgeted for the 2007-2013 period were spent, but this took until 2017. By the start of 2020, the approval of projects for the structural and investment funds reached 91% of the envelope for the 2014-2020 budget period (3).

The present note looks at the apparent low absorption of EU funds. The EU budget is a slow vehicle at the best of times, and that the EU’s recovery fund has overloaded it with an inappropriate function of countercyclical macroeconomic stimulus. The recovery fund would be more effective as a standing facility for increasing the rate of public investment rather than a one-off.

The progress of the 2014-2020 structural funds

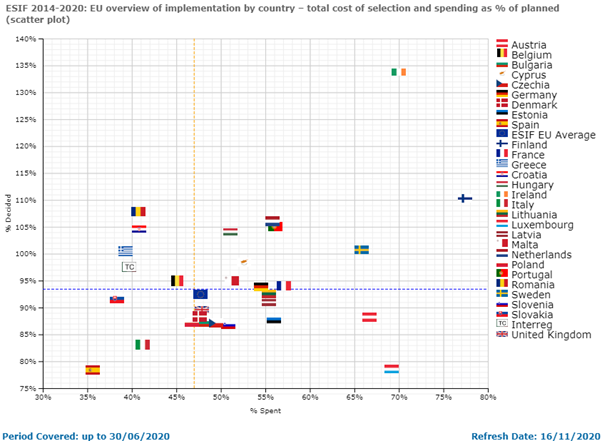

According to the EU’s open data portal, 94% of the budgeted European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) had been allocated by the end of June 2020, and 47% spent (2). This means 50% of the funds allocated had been spent. This is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: allocation and spending of structural funds relative to budget, by member state (European Commission)

Despite this, the experience of the 2007-2013 budget period suggests that fund absorption by member states is likely to catch up to nearly 100% eventually.

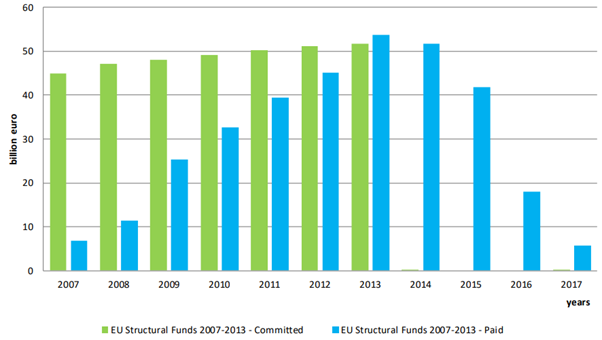

Figure 2 illustrates that, by the end of 2013, less than two-thirds of money committed in the 2007-2013 budget period had been absorbed as payments (5). In the end, however, the Commission reported an absorption level of 97% for 2007-2013, 2 percentage points higher than in the previous budget period. The spending profile with a long tail after the eligibility period is similar to what we estimates for the expected spending profile of the EU’s recovery plan in a previous note (4).

Figure 2: spending pattern of 2007-2013 European structural funds (European Court of Auditors)

Spending lags are behind low fund absorption

There are several reasons why absorption of structural funds should be expected to be slower in the 2014-2020 budget period compared with the previous budget period (6).

The first is that the spending rule is N+3 years, compared to N+2 previously. This means budget execution is naturally slower as there will be one more year to spend what is committed.

The second is that the so-called General Regulation, the legislative framework for the structural funds, was adopted with a five-month delay for the 2014-2020 period. The 2007-2013 General Regulation was adopted in July 2006, nearly six months prior to the start of the budget period, but the 2014-2020 regulation was adopted in December 2013. Member states then delayed the approval of their operational programmes. The Covid-19 pandemic, as well as the introduction of the Next Generation EU recovery fund, have delayed the approval of the next budget. The Polish and Hungarian veto of the rule-of-law linkage now threatens to delay approval beyond the end of the year, so the 2014-2020 budget might need to be rolled over. Fortunately in the case of the recovery fund, many member states have already prepared draft recovery and resilience plans.

A third reason is that, as illustrated by figure 2, there is significant spending from one budget period during the initial years of the next. This overlap reduces the urgency to execute the new budget.

The fourth reason is pre-financing, which refers to EU programme funds disbursed before projects are approved. Pre-financing in 2014-2020 is about 7% of the total budget, which is higher than in the previous budget period. The Commission argues that higher pre-financing also reduces the pressure for speedy execution of projects (6). Though we find this argument weak, the pre-financing rate of the Recovery and Resilience Facility has been set at 10% which is even higher. More funds will be disbursed earlier but, if the Commission is correct, the higher pre-financing may work to reduce the urgency to implement recovery and resilience plans.

Some member states have persistent low absorption

The issue of low absorption of EU funds had been identified already by the 2007-2013 budget period. In 2014, the Commission set up a Task Force for Better Implementation (TFBI) intended to help the countries whose fund absorption rate for the 2007-2013 was below average, namely Italy, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechia, Slovakia, and Croatia (5). This task force was able to substantially increase absorption of funds by these countries in the years following the end of the eligibility period. Expenditure of funds was subject to the N+2 rule, so it could continue until 2015 and indeed it continued until 2017 according to figure 2.

The success of the TFBI led to the creation of a permanent Better Implementation Unit at the European Commission. However, as we shall see, there is a group of countries which repeatedly rank low in fund absorption, which suggests structural problems have not yet been solved by the Better Implementation Unit.

In 2018 the ECA conducted a study on the causes of persistent low absorption in the 2014-2020 budget period (7). This involved a survey of the member states with the lowest levels of absorption by the end of 2017, namely Italy, Spain, Slovakia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Malta. The member states surveyed by the Court of Auditors confirmed the reasons given by the Commission for low fund absorption. These were:

- delayed adoption of legal acts and guidance for the 2014-2020 operational programmes and of the member states’ operational programmes themselves, as well as delays in meeting ex-ante conditionality for the operational programmes;

- delays in designating national authorities and in auditing this designation;

- knock-on effects from the delayed absorption of EU funds in the 2007-2013 budget period and its late closure; and

- reduced urgency from the shift from N+2 to N+3 year rules for disbursement of committed funds.

Spain lags because of low project generation

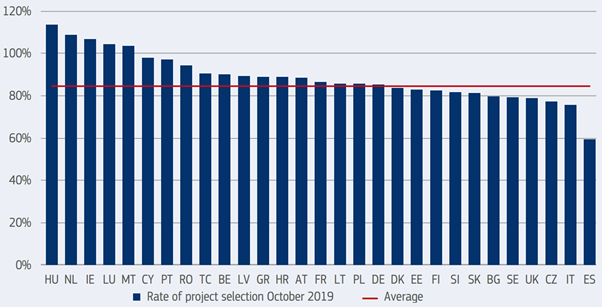

Figure 1 shows that, even though 94% of budgeted structural and investment funds had been committed EU-wide by mid-2020, this figure varied widely among member states. Spain and Luxembourg were the two countries with the lower rate of fund commitment, about 80%, followed by Italy with 84%. While Luxembourg had spent almost 85% of the committed funds, Spain and Italy had spent about 45% of committed funds, which is in line with the EU average. Spain therefore lags in absorption of EU funds because of a low rate of project approval, rather than due to delays in the execution of projects once they are approved. This is borne out in figure 3 which shows that, in October of 2019, Spain was clearly a negative outlier in the fraction of the budget committed to selected projects for the combination of structural and investment funds, regional development funds, cohesion funds and the youth employment initiative (3).

Figure 3: project selection by member state (European Commission)

As we can see from figure 3, Italy and Spain have the lowest rates of project selection. Of the six countries involved in the 2018 survey because of their low fund absorption, they are the only two that remain among the countries with the lowest rates of project selection two years later. Bulgaria and Croatia were involved in the 2015 TFBI on account of low fund absorption in the previous budget period, and at the end of 2019 they are once more among the countries with the lowest rate of project selection in the current budget period. We observe that Italy, Slovakia, and Croatia had low absorption both in 2013 and in 2017. All of this points to unsolved structural problems in these countries.

If we had to hazard a guess as to why Spain stands out as an outlier in project selection for the 2014-2020 budget period, when it was above average in fund absorption in 2007-2013, we would attribute it to the repeated failure to pass annual budgets in a timely manner since 2016. This is due to political fragmentation in the Spanish parliament after the December 2015 general election. In fact, Spain is still operating under the rolled-over budget for 2018, which was itself approved late.

Concluding remarks

The debate around the effect of the EU’s recovery fund has focused on the low rate of absorption of EU funds. But this is only an appearance. EU funds are rather spent slowly, which leads to a current absorption rate below 50% for the present multiannual budget period. Ultimately, however, most of the funds in the previous multiannual budget were absorbed. The real issue, which also explains differences between countries, is the timely generation of a projects eligible for EU funding.

Structurally-low absorption of EU funds affects countries some of which are expected to be the biggest beneficiaries of the recovery fund, namely Bulgaria, Croatia, Italy, Slovakia and Spain. This is due to the long delays in these countries to approve legal instruments, designate competent authorities, and design operational plans.

On the other hand, slowness in the disbursement of EU funds is structural. The so-called N+3 year rule has to do with the multi-year nature of the individual investments funded by EU funds. The overlap of the N+3 disbursement period of one budget with the eligibility period for the next budget is not a problem for the stability of investment flows, but it does hinder the speedy absorption of funds from individual EU programmes.

These considerations suggest that the EU budget is an ill-suited tool for deploying macroeconomic stimulus on a short notice. Rather, it is better suited for sustaining a level of spending. The eurozone does need to raise its net public investment, and the EU’s recovery fund seems suitable for that purpose. But it has been legislated as a one-off economic stimulus tool to kick-start the recovery of the EU’s economy after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Slow absorption of structural funds can be addressed through institutional reforms, however. Some member states which lag in fund absorption, notably Spain, are speeding up their administrative reforms in anticipation of the need to process a substantial amount of recovery fund money. If countries reform their project approval and front-load spending it is still conceivable that the recovery fund may end up serving as a countercyclical stimulus.

References

1. Darvas, Zsolt. Will European Union countries be able to absorb and spend well the bloc’s recovery funding? Bruegel Blog. [Online] 24 September 2020. https://www.bruegel.org/2020/09/will-european-union-countries-be-able-to-absorb-and-spend-well-the-blocs-recovery-funding.

2. European Commission. EU Overview. European Structural and Investment Funds. [Online] 16 11 2020. https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/overview.

3. —. Analysis of the budgetary implementation of the European structural and investment funds in 2019. Publications Office of the EU. [Online] 13 May 2020. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/f39e0146-958c-11ea-aac4-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-128790030.

4. Carrión Álvarez, Miguel. The EU recovery plan: funding arrangements and their impacts. Funcas. [Online] August 2020. https://www.funcas.es/articulos/the-eu-recovery-plan-funding-arrangements-and-their-impacts/.

5. European Court of Auditors. Special report no 17/2018: Commission’s and Member States’ actions in the last years of the 2007-2013 programmes tackled low absorption but had insufficient focus on results. [Online] 13 September 2018. https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=46360.

6. —. Annual reports concerning the financial year 2019. [Online] 10 November 2020. https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=53898.

7. —. Annual reports concerning the financial year 2017. [Online] 4 October 2018. https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=46515.