Eurozone fiscal reform in light of Covid-19: a review of existing proposals

Fecha: marzo 2021

Miguel Carrión Álvarez, Funcas Europe

The European Commission recently issued a communication to EU member states to clarify its medium-term fiscal policy stance (1). This is necessary because the ongoing suspension of the EU’s fiscal rules presents member states with considerable uncertainty over the normative context of their medium-term budget plans. The European Semester process requires member states to submit to the Commission three-year budget plans, as part of the forward-looking national reform and stability/convergence programmes due at the end of April (2). But, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the European Commission triggered the general escape clause of the stability and growth pact last year. The general escape clause continues to apply in 2021, and it makes a material difference to member states’ budget planning whether the fiscal rules will apply or remain suspended in 2022 or 2023. The Commission, while not binding its future decisions on the general escape clause, is giving member estates some guidance on what to expect and will evaluate the 2021 stability or convergence plans accordingly.

The Covid-19 crisis is thus throwing into sharp relief the implications of the stability and growth pact and the fiscal compact in the face of a genuine external shock. While the European Commission is being flexible in its interpretation of fiscal sustainability, it is not addressing the deeper and thornier issue of whether EU fiscal rules need to be reformed or not, and, if so, what should be the directions of change.

The purpose of this note is to review recent proposals for reform of the European fiscal rules. Thus, the note does not address the case for an unchanged policy regime. Neither does it examine the various statements made recently by the Commission concerning the flexible application of the rules during the pandemic.

We take as the cut-off date the latest appraisal of the issue of fiscal rule reform by Funcas, made in 2018 by Raymond Torres in the SEFO journal (3). We then divide the subsequent proposals into two groups: those made in 2019 and early 2020, before the start of the Covid-19 crisis, and those made in the context of the pandemic. A proposal co-authored by Olivier Blanchard has a special place in this. Not only is it the most prominent, but also it spans the two periods as it is outlined in a mid-2019 column by Blanchard (4) and has gone through several versions until last month (5).

1. When to lift the general escape clause?

The concern underlying the Commission’s communication is that the fiscal impulse necessary to overcome the Covid-19 crisis and support the subsequent recovery may jeopardise fiscal sustainability. This tension is reflected in the communication when it notes that risk premia on EU government debt remain low, but that this could change if either fiscal support is withdrawn prematurely or the commitment to preserve medium-term fiscal sustainability is abandoned. The Commission is implying that debt markets expect governments to keep fiscal policy expansionary in the short term, but to tighten it in the medium term. From this point of view, the policy question is to time properly the transition from expansionary to tight fiscal policy.

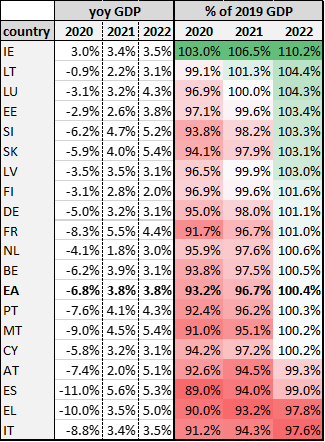

The European Commission expects EU real GDP to recover to its pre-Covid level by mid-2022. However, there are significant differences between countries. Some member states will reach their pre-crisis output by the end of 2021 while some others will not achieve this even by the end of 2022. Table 1 reflects the figures from the Commission’s Winter Economic Forecast (6).

Table 1: European Commission Winter Forecast, 2021

The Commission concludes that the EU’s overall fiscal stance should remain expansionary in 2021 and 2022. Member states should use the Recovery and Resilience Facility to continue to support their economies while improving their fiscal positions. This must be understood to refer primarily to the grants component of the RRF, as that will not contribute to the national debt or deficit ratios. The loans component will help contain deficits, in so far as it will reduce debt servicing costs by being priced favourably relative to issuing bonds to the market.

The main quantitative criterion affecting a decision to stop applying the general escape clause would be the overall level of output in the EU compared to the end of 2019. The official communication to the member states does not spell this out, but the attached frequently-asked questions strongly suggests it (7). As shown in Table 1, EU GDP in 2022 is expected to be 100.4% of 2019 GDP. Accordingly, the Commission expects to continue to apply the general escape clause in 2022 but to lift it in 2023. Austria, Spain, Greece, and Italy are the countries whose GDP is expected to remain below the end-2019 level at the end of 2022. Crucially, according to the Commission, once the general escape clause is lifted, all the flexibility in the Stability and Growth Pact will still be used for those member states that have not recovered to pre-crisis levels of activity. This means the debt brake included in the fiscal compact will not start applying to member states until they exceed the 2019 GDP level. Once output gets back to this level, however, member states will be required to run sizeable primary surpluses by operation of the debt brake attached to the Fiscal Compact. The implied primary surpluses will be larger than before the Covid-19 crisis, to compensate for the debt incurred to deal to deal with the pandemic. As a result, overall real growth in the eurozone is likely to stagnate once it reaches the 2019 level.

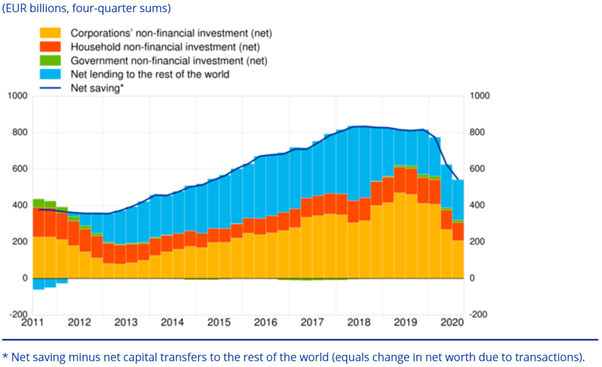

Even before the Covid-19 crisis, the European fiscal rules were being brought into question. The main charge that can be levied against the fiscal rules is that the debt brake has not been implemented as designed and, even then, the fiscal rules have resulted in a collapse of public-sector investment, as can be seen from Figure 1.

Figure 1: eurozone investment by institutional sector (ECB, 2021)

Moreover, Figure 1 shows that, during the Covid-19 crisis, business investment has dropped significantly, and this without a compensatory increase in public investment despite a massive expansion of public deficits (8). In fact, net public investment remains stubbornly stuck close to zero for over eight years now.

2. Pre-pandemic fiscal reform proposals

The first proposal we consider was prepared by Bruegel for the French Council for Economic Analysis (9). It argues that the EU fiscal rules suffer from practical and conceptual weaknesses. The first is that they are unresponsive to a scenario of protracted recession, as they at best postpone or slow down fiscal tightening when it might be inappropriate in a persistent economic slowdown. Conceptually, the rules are based on the idea of the structural budget balance, which is superficially appealing but is unobservable as it depends on an estimate of the gap between actual and potential output. Moreover, it has been known from early on that revisions to estimates of the output gap are of the order of 0.5-1.0% for advanced economies, and even larger in the case of more highly-indebted countries. Drawing heavily on a noted proposal by a group of 14 Franco-German economists (10), the Bruegel proposal is for an expenditure rule aiming to achieve a target debt-to-GDP ratio. Fiscal policy would start with a medium-term debt-reduction target. This would imply a medium-term nominal GDP growth projection and a medium-term expenditure path, which would be used to set a spending ceiling for the following year. Nominal expenditures would be net of interest payments, non-discretionary unemployment benefits, discretionary revenue measures. Public investment would be accounted for on an amortised basis. Deviations between actual and budgeted spending would go in and out of an adjustment account. An escape clause would still be needed to account for extreme events such as the global financial crisis.

| proposal | problems | solutions |

| Darvas et al. / Bruegel / French Council of Economic Analysis |

|

|

| European Central Bank working paper |

|

|

| Beetsma & Lasch / European Fiscal Board |

|

|

| Blanchard / Leandro / Zettelmeyer |

|

|

| Fargnoli |

|

|

| D’Elia |

|

|

The second proposal is contained in an ECB working paper on the fiscal rules in the first 20 years of the monetary union (11). The paper argues that the Stability and Growth Pact is not steering the aggregate fiscal stance of the eurozone, as well as not being enforced consistently which leads to insufficient ability to stimulate the economy in economic slowdowns. In addition, countries with fiscal space are not compelled to make use of it. The fiscal framework is criticised for being overly complex because of successive political compromises devised to address its shortcomings when dealing with specific macroeconomic circumstances. More than a single coherent reform scheme, the paper proposes several principles for reform. These include: improving the internal coherence of the fiscal framework itself, which consists of a deficit ceiling, a debt target, and a medium-term objective of approximate budget balance over the business cycle; simplifying the fiscal rules and reducing its reliance on structural balance or output gap estimates; shifting incentives from sanctions for noncompliance to rewards for compliance; incorporating the aggregate fiscal stance of the eurozone. On the balance of sanctions and rewards, the paper reflects discussions of making a multi-year record of compliance with the fiscal rules a condition of access to various EU financial assistance facilities. It is politically easier to withhold access to EU structural funds, say, than to impose a fine on a country that is failing to comply with the fiscal rules.

Third, in a short policy paper, Roel Beetsma and Martin Lasch of the European Fiscal Board propose a central fiscal capacity as the necessary compromise between advocates of what they call fiscal risk-sharing and risk-reduction (12). According to them, economists generally advocate reform of the fiscal rules along the lines outlined previously, while policymakers are wary of the possibility that fiscal framework may not be improved by political negotiations on its reform. Policymakers tend to advocate implementing the existing rules, with “greater determination and less politics”. Beetsma and Lasch argue that a central fiscal capacity is necessary for proposals to reform and strengthen the fiscal rules to be accepted by those who would like to see greater sharing of the costs of economic downturns. A central fiscal capacity could also strengthen fiscal discipline if access to it is made conditional on compliance with the fiscal rules.

Fourth, Olivier Blanchard, the former IMF chief economist, suggested in a 2019 opinion piece that the EU should get away from micro-managing the fiscal policies of member states with increasingly complex rules motivated by the assumption that governments tend to misbehave (4). Instead, the Commission should evaluate the sustainability of member states’ fiscal trajectories, and let bond markets provide discipline. In addition, fiscal policy coordination cannot be left to the aggregate of the member states acting independently. There needs to be a way for member states to commit together to a larger fiscal expansion when needed, or else a central fiscal capacity funded by Eurobonds which can then finance higher spending by the member states.

Blanchard then teamed up with Álvaro Leandro and Jeromin Zettelmeyer to propose a transition from currently unenforceable fiscal rules to presumably enforceable fiscal standards (13). This would be coupled with the adoption of capital budgeting to protect public investment in a downturn, and the creation of a central fiscal capacity to support aggregate demands when monetary policy in constrained.

The shift from rules to standards is legal terminology, where “rules” are clear, abstract, and laid down in advance; whereas “standards” are principles intended to accommodate particular circumstances. The reasons why they see a transition from rules to standards as necessary is two-fold. First, the prospect of a persistent low interest-rate environment, in the context of economic slowdown in the EU that preceded the Covid-19 pandemic, changed the trade-off between the costs of a high debt ratio and depressed aggregate demand. Second, the fiscal rules would need to become more, not less, complex to incorporate the EU-level output gap, monetary policy, and growth expectations.

Fifth, in a working paper, Raffaele Fargnoli considers the political economy of an incomplete monetary union, where the process of reforming the fiscal framework is tied with the necessary creation of new institutions (14). He argues that a larger central fiscal capacity both reduces the need for national macroeconomic stabilisation and makes it more politically palatable to impose strict fiscal rules at the state level. He then proposes a framework in which member states would submit medium-term economic plans including a debt target which would then be negotiated with EU-level institutions. Enforcement would be a system of graduated penalties to deal with gross policy errors resulting in deviations between member-state policies and EU policy recommendations.

Sixth, in an opinion piece, Enrico D’Elia argues that the fiscal rules should compare debt and deficit to government revenues, not to GDP (15). The main argument for this is that debt sustainability depends directly on current and future government revenues, not on the size of the economy. One of the advantages for D’Elia is that such accounting would penalise tax cuts over spending increases, which he argues is in line with the respective multiplier effects on economic growth.

4. Post-pandemic fiscal reform proposals

In the course of 2020, the focus of fiscal reform discussions shifted from the low-interest-rate environment to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Table 3: post-pandemic fiscal reform proposals

| proposal | problems | solutions |

| Pekanov & Schratzenstaller / European Parliament | restriction of green investment |

|

| Truger | post-pandemic fiscal tightening |

|

| European Fiscal Board | slow reaction to external shock |

|

| Blanchard / Leandro / Zettelmeyer | radical uncertainty |

|

A study commissioned by the Economic Affairs Committee of the European Parliament, on the interaction of the EU’s fiscal framework and its green transition goals, already considers explicitly the increased investment needs resulting from the Covid-19 crisis, as well as the Recovery and Resilience Fund (16). The study argues that the high investment needs of the green transition justify exempting green public investment from the fiscal rules. Alternatively, they propose a green golden rule for investment, or for the European Commission to set country-specific shares of government spending to the dedicated to green investment. Green investment would be identified as gross fixed capital formation meeting the criteria for inclusion in the EU’s sustainable investment taxonomy. The Stability and Growth Pact already has an investment exemption, which allows short-term deviations from the fiscal targets. To incentivise green investment, the proposal would be to allow longer-term deviations from the fiscal targets due under a new green-investment exemption. A golden rule for investment generally takes the form of separating government expenditure into current and capital expenses and exempting capital expenditure from the fiscal rules. This has not been implemented in the European fiscal rules. The proposal would be to introduce a golden rule but only for green investment.

Achim Truger argues, like we did above, that neither the eurozone as a whole nor the so-called crisis countries can afford the fiscal tightening that will result from the reinstating of the fiscal rules after the expected increase in government debt ratios because of the Covid-19 crisis (17). He proposes to increase the cyclical leeway of fiscal policy in one of two ways. The first would be to change the European Commission’s method to estimate the structural budget balance. This is based on the output gap which is unobservable but is known to be underestimated in a downturn, leading to an over-estimate of the structural deficit and a cyclical restriction of fiscal stimulus. A second option would be to change the limits of the stability and growth pact to take account of the impact of the Covid-19 crisis. For instance, the debt limit could be raised from 60% to 90% of GDP. This would be commensurate with the expected increase in the eurozone’s debt ratio because of the pandemic. The deficit limit of 3% could be adjusted upwards accordingly. Truger also favours a golden rule, perhaps weighted by the marginal returns of different kinds of investment, as well as an expenditure rule to replace the structural budget balance concept. Spending would be allowed to increase by the medium-term real growth rate plus the ECB’s inflation target, and this could be coupled with a golden rule exempting investment from the spending limits.

Considering the Covid-19 crisis, the European Fiscal Board argues that the eurozone needs a standing central fiscal capacity, a reformed fiscal framework, and a golden rule for investment (18). The Covid-19 crisis has shown the cost of a central fiscal capacity not being available to be deployed in a timely manner. Instead, a year has been used setting up a one-off recovery plan, Next Generation EU. The central fiscal capacity should be embedded in an EU budget financed by its own tax resources, be able to borrow in response to an external shock, and focus on EU investment priorities. The fiscal framework should be reformed by adopting a country-specific debt anchor, an expenditure rule to replace the debt brake, and preserving the general escape clause. And finally, growth-enhancing investment should be protected from spending limits. The EFB shows that, for instance in the case of Italy, the expenditure rule would allow for higher spending and a slower debt reduction in the initial years of recovery after the pandemic, but in the longer run it would lead to a faster convergence to the debt anchor if growth improves.

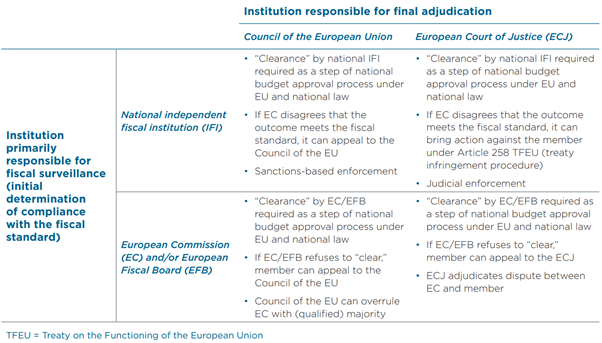

Table 4: EU fiscal standard enforcement options (Blanchard e.a., 2021)

Finally, Blanchard, Leandro and Zettelmeyer have revised their proposal considering the Covid-19 crisis (5). The result is a sharper focus on the shift from rules to standards, since the pandemic has shown conclusively that it is unreasonable to expect rules to address in advance all the possible situations that fiscal policy may face. It has also shown that a large external shock can present an unsolvable trade-off between macroeconomic stabilisation and debt sustainability. The Covid-19 crisis is an example of why it is impossible to design hard-and-fast rules that get the trade-off right in advance. The recovery fund constitutes a form of fiscal union, which makes reform of the fiscal rules a more pressing concern. But also, the authors assume the central fiscal capacity that the recovery fund represents will not be expanded. The argument for reforming the fiscal rules has become even stronger. They were designed to preserve fiscal sustainability in an environment of low debt and high interest rates, but the European economy will emerge from the Covid-19 crisis with high debt and low interest rates. One important point of the fiscal standards they propose is to stay away from trying to force member states to run more expansionary policies than they wish to. When shifting from rules to standards, one important question is how standards are enforced. The authors argue transparency and accountability to national parliaments is unlikely to work in the context of a monetary union with significant cross-country externalities. Market discipline has been insufficient, and the political will for the necessary government debt restructurings may not be there in the future. The alternative is a pair of institutions, one responsible for fiscal surveillance and another responsible for adjudication of compliance with the fiscal standards. Fiscal surveillance can be carried out at the national or European level, and adjudication could take place in the European Council or in an independent judicial institution such as the European Court of Justice. These options are summarised in Table 2.

5. Summary and conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic has sharpened the focus of criticism of the European fiscal rules. Previously, the argument revolved around reform and implementation. But the pandemic is a genuine external shock and the stronger fiscal tightening that higher debt ratios imply when the debt brake is reinstated can hardly be justify on the moral failing of indebted countries. As a result, post-pandemic arguments for reform get away from technical discussions of the complexity and reliability of the fiscal rules.

The elements of the proposed reforms have not changed, though. In the short term, the simplest adaptation is to update the fiscal targets so that higher public-debt ratios do not result in a stronger fiscal tightening than would have taken place without the pandemic. More far-reaching proposals for reform of the fiscal rules involve replacing the current focus on the structural budget balance with debt sustainability assessments and expenditure rules. There also seems to be broad agreement on the need for investment exemptions or golden rules, with green investment perhaps singled out for protection. The most radical reform proposal seems to be that of Blanchard and his co-authors, who advocate giving up on fiscal rules altogether in favour of qualitative standards. Though this is justified on grounds of radical uncertainty which has become easier to argue considering the Covid-19 pandemic, the issue arises as to the practicality of such a system in the absence of clear-cut targets.

It remains to be seen however, whether enough political impetus exists for a major overhaul of fiscal rules. Another thorny issue, not addressed in the present comparative paper, is the relative merit or de-merit of any change vis-à-vis an improved application of existing fiscal rules. For all these crucial issues much depends, among other factors, on the relative fiscal positions of different countries as they come out of the pandemic crisis.

References

1. European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the Council - One year since the outbreak of COVID-19: fiscal policy response. Eur-Lex. [Online] 3 March 2021. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2021%3A105%3AFIN.

2. —. National reform programmes and stability or convergence programmes. Business, Economy, Euro. [Online] 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-economic-governance-monitoring-prevention-correction/european-semester/european-semester-timeline/national-reform-programmes-and-stability-or-convergence-programmes.

3. Torres, Raymond. European fiscal policy: Situation and reform prospects. SEFO (Funcas). [Online] 2018. https://www.sefofuncas.com/Spains-revised-fiscal-outlook-and-key-challenges/European-fiscal-policy-Situation-and-reform-prospects.

4. Blanchard, Olivier. Europe Must Fix Its Fiscal Rules. Project Syndicate. [Online] 10 June 2019. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/eurozone-must-relax-budget-deficit-rules-by-olivier-blanchard-2019-06.

5. Blanchard, Olivier, Leandro, Álvaro and Zettelmeyer, Jeromin. Redesigning EU fiscal rules: From rules to standards. Peterson Institute for International Economics. [Online] February 2021. https://www.piie.com/publications/working-papers/redesigning-eu-fiscal-rules-rules-standards.

6. European Commission. Winter 2021 Economic Forecast: A challenging winter, but light at the end of the tunnel. Press Corner. [Online] 11 February 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_504.

7. —. Questions and answers: Communication on fiscal policy response to coronavirus pandemic. Press Corner. [Online] 3 March 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_21_885.

8. European Central Bank. Euro area economic and financial developments by institutional sector: third quarter of 2020. Media. [Online] 28 January 2021. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/stats/ffi/html/ecb.eaefd_full2020q3~f08970761d.en.html.

9. Darvas, Zsolt, Martin, Philippe and Ragot, Xavier. European fiscal rules require a major overhaul. Bruegel. [Online] 24 October 2018. https://www.bruegel.org/2018/10/european-fiscal-rules-require-a-major-overhaul/

10. Bénassy-Quéré, Agnès, et al. Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform. Centre for Economc Policy Research. [Online] 2018. https://cepr.org/active/publications/policy_insights/viewpi.php?pino=91

11. Kamps, Christophe and Leiner-Killinger, Nadine. Taking stock of the functioning of the EU fiscal rules and options for reform. European Central Bank. [Online] August 2019. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op231~c1ccf67bb3.en.pdf

12. Beetsma, Roel and Martin, Larch. EU Fiscal Rules: Further Reform or Better Implementation? IFO Institute. [Online] 2019. https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/07-11_FO_Beetsma_Larch_0.pdf

13. Blanchard, Olivier, Leandro, Álvaro and Zettelmeyer, Jeromin. Revisiting the EU fiscal framework in an era of low interest rates. European Fiscal Board. [Online] 9 March 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/s3-p_blanchard_et_al_0.pdf

14. Fargnoli, Raffaele. Adapting the EU fiscal governance to new macroeconomics and political realities. European University Institute. [Online] March 2020. https://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/65770

15. D'Elia, Enrico. Reforming Europe’s fiscal rules. Social Europe Journal. [Online] 24 March 2020. https://www.socialeurope.eu/reforming-europes-fiscal-rules

16. Pekanov, Atanas and Schratzenstaller, Margit. The role of fiscal rules in relation with the green economy. European Parliament. [Online] 31 August 2020. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=IPOL_STU%282020%29614524

17. Truger, Achim. Reforming EU Fiscal Rules: More Leeway, Investment Orientation and Democratic Coordination. Intereconomics. [Online] 2020. https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2020/number/5/article/reforming-eu-fiscal-rules-more-leeway-investment-orientation-and-democratic-coordination.html

18. Thygesen, Niels, et al. Reforming the EU fiscal framework: Now is the time. VoxEU. [Online] 26 October 2020. https://voxeu.org/article/reforming-eu-fiscal-framework-now-time